Post COVID-19 Lockdown Business Context: Navigating Strategic and Organizational Choices

Summary

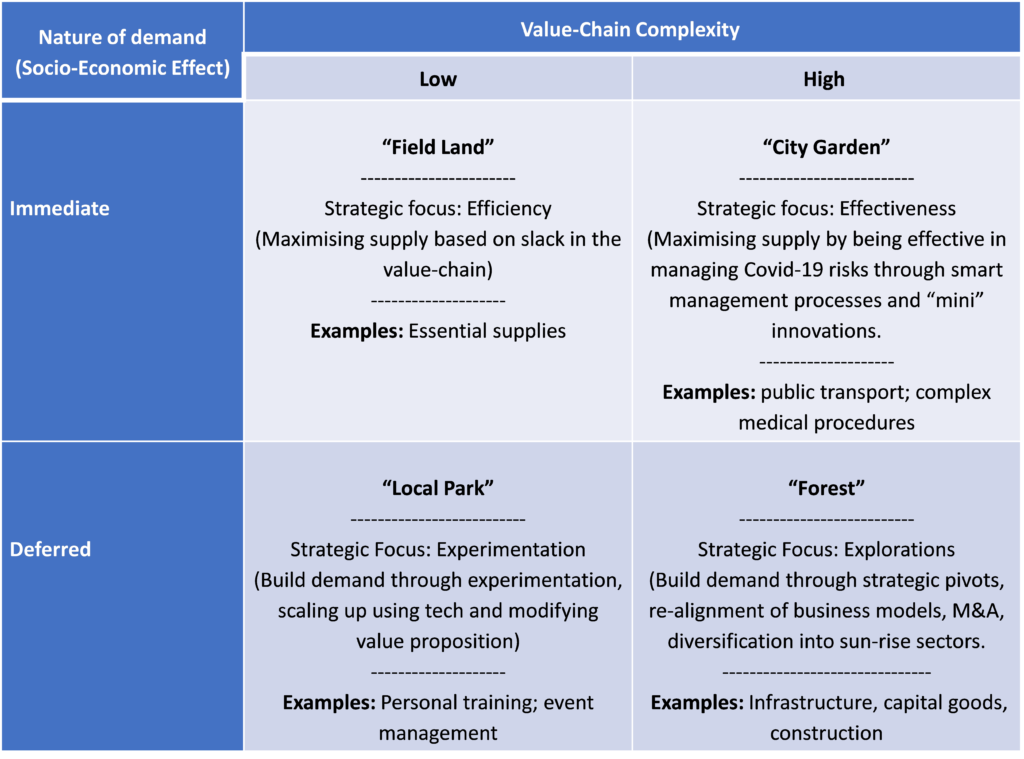

The paper seeks to explore strategic choices available to firms in the post Covid-19 lockdown period. Using Schön’s approach, this paper characterises the post lockdown as an indeterminate situation, and argues that an effective approach needs emphasis on both, “problem-setting” as well as “problem-solving”. It draws attention to the distinction between risk and uncertainty, and argues that effective management in the post Covid-19 situation requires correctly encoding the challenges as risks or uncertainty, and then making appropriate choices. A strategic choice framework using value-chain complexity and socio-economic effects of demand as two dimensions is proposed. It identifies four types of strategic categories (namely, farm fields, city gardens, local-park, and forest). For each of the four categories, a dominant strategic focus is identified from a set of 4Es (Efficiency, Effectiveness, Experimentation, and Exploration). It notes that in the post lockdown phase, leaders will face an important choice on whether to use “value extraction” or “value creation” strategy, particularly in matters of employee and customer relations

Introduction

COVID-19 is considered one of the biggest crises that humanity has faced in our living memory. Given the uncertainty and complexity associated with prevailing social and economic conditions and the broad impact the virus has had on our lives, it is not surprising that there is already an on-going debate on its’ various implications in the post lock-down context. The purpose of this article is to build on these debates, but at a more granular level of business and organizational behaviours. Economic activity takes place through organizations, and therefore “what”, “how” and “why” of business behaviour matters, particularly in the current context. It is hard, if not impossible, to speculate on what the “new normal” will look like, but we have a better chance to shape it in the desired direction, if we engage in a debate at the right time. This note seeks to share few ideas and develop this debate further.

1.0 Post COVID-19 Lockdown: An Indeterminate Economic Context

In an extreme and unfortunate way, the Covid-19 crisis has challenged our thinking about risks and uncertainty, decision-making with imperfect information, the definition and measures of success, role of time and speed in decision making, and unknown – and unfortunate – trade-offs (human life Vs human suffering Vs economy). Though management theory covers most of these aspects (except the trade-off between human life and economy, which falls mostly in domains of ethics and moral choices), the scale, complexity, scope, and, importantly, the salience of its’ moral aspects make this crisis unique in more than one way. The different choices being made by various governments convey the priorities, uncertainties and risks as well as decision premises that business leaders may have to consider in the post lock-down period. These elements together give rise to what Schön[1] referred to as indeterminate situation. Schön defines an indeterminate situation to be characterised by complexity, uncertainty, stability, uniqueness and value conflict.[2]

Schön argues that a professional, more often than not, faces an indeterminate swampy zone of practice where the problem cannot be solved by applying theory and technique derived from scientific knowledge[3]. While discussing the role of professional practice from technical rationality perspective, Schön mentions that the professional practice’s emphasis on problem solving ignores ‘problem setting’, which is an important part of dealing with an indeterminate situation in an effective way. This approach suggests to not only engage in reflections as to the nature of context, problem, and framework to use, but also undertake “problem-setting” in its’ own right as a key component of strategic thinking and leadership.

2.0 Covid-19: “Problem-Setting”

A “normal” discussion on the economic, social and business future aims to predict what the new normal will look like, and perspectives differ with two end points of the spectrum being, not much will change and a system re-boot (if not re-set). These perspectives, however, assume that there is no major second wave, that there is a set expiry date (or time-window) for the Covid-19 crisis to end, and there will be a steady-state after the crisis. This scenario approach, which involves a premise that planning is largely a prediction and problem-solving approach, is labelled here as determinate situation.

An alternative approach is to consider post-lockdown situation as an indeterminate (for now), with uncertainties on whether second-wave could become a major risk; there may or may not be an end to the severity of crisis in the foreseeable future (there is already limited discussion on whether or not vaccine is possible, though everyone hopes it does); that the “new normal” will be evolutionary, emergent and transitionary, and this emerging normal will unfold and experienced differently at various economic, social, business and individual levels. In dealing with indeterminate situation, we think critically about the thinking that led to a surprise opportunity or a challenge emerge, which, in turn, results in the restructuring of strategies or ways of framing or the understanding of the phenomenon itself[4].

2.1 Risk and Uncertainty

Noted economist Frank Knight made a distinction between risk and uncertainty by noting that risk situations allow for computation of probabilities (of risk-events), while uncertain situations do not. A determinate situation is more likely to involve risk management, while indeterminate situation leans towards managing under uncertainty. At a general level, the financial implications (to public) of Covid-19 crisis are a risk (i.e., one can calculate when the bills become due and how much cash one has to meet the expenses), while Covid-19 infections present an uncertainty (an individual may or may not get infected; more or may become ill; may or may not have life-threatening consequences; it depends on various factors). At the risk of over-simplification, risk management is about developing plans and processes to deal with probabilities of various risk events happening; managing under uncertainty is about taking the consequences as the start point, and developing plans backwards to address unwanted consequences (since probabilities are not known).

How business leaders encode a problem (risk as opposed to uncertainty) influence the mental models, decision frameworks, criteria and choices made. Situations framed and managed as risky, whilst they are uncertain, could have different strategic, operational and cultural implications than if they are managed as uncertainty. Post Covid-19 lockdown may present business leaders with situations that will need mental models that make this distinction salient.

3.0 Emerging Economic and Business Situation

Though the specific details of the emerging economic and business context are hard to predict and will have “surprise” elements, it is useful to consider few factors that could influence the choice of scenarios that business leaders adopt.

The role, potential consequences and practicality of easing an extensive lock-down remains a matter of debate , given that, some would argue, curve seems to have flattened, the economic costs are rising, and social fatigue with it seems to be building up. This is challenged by a different perspective that suggests that the real cause was pandemic, lockdown was a choice and economic collapse was the effect of that choice. The policy implication is that despite the extreme economic cost, there is a business case to contain the virus first[5]. The debate remains important, even as the economic imperatives become salient, and points to the uncertainty posed by the interaction effects between economic challenges, Covid-19 risks, and lockdown. One of the unknowns will be how these three variables change, their interaction effects on each other, and how the economic and social landscape may dance, because of the simultaneity of these three variables in action.

The secondary economic and social effects of Covid-19 crisis and the lockdowns are also indeterminate, and will influence business leaders’ choice of scenarios and strategies. While the loss of business, impact on jobs, and economic contraction remain a common knowledge, what is not known are the different ways in which mid- to long term consequences of lock-down behaviours may show up, and how light or severe they could get in the months to follow. This will depend on the perceived risks and preparedness for the second wave. It seems most probable that there will be a phased opening of economy in different parts of the world (Denmark and Germany already have started), though various factors (such as timing, scope and breadth of it) may influence the trajectory of economic revival in the near future. Once the lock-down is relaxed, different formats of lock-down (in different countries) may lead to different kinds of economic, social and business related secondary effects. Though the economic trajectories and social priorities/constraints of various countries (and regions) were different previously as well, they were at least known. Two specific implications, local business behaviour and social attitudes, are discussed below.

- The globalisation of economy in the last two decades created efficient supply-chains that traverse through various regions and countries. These supply chains, importantly, also include global manpower supply chains, which feed into the talent plans of global firms. These regions and countries were subject to different types of lock-down, and likely to follow different approaches to lock-down easing. This may, in short to mid-term, lead to “lock-down arbitrage” seeking behaviours, and in the long run, assuming Covid-19 crisis or its’ effects remain salient, trigger an interest in local or regionally based supply-chains. It is also likely that given the cheap asset prices, particularly in hard-hit countries and regions, there will be an interest in take-overs or mergers, including cross-country M&A activities.

- While two months are not enough for individual habits and social norms to change permanently, they are long enough for the balance between economic needs and health risk to change. In the post-lockdown context, there will be expectations, if not requirements, on the social distancing and behaviour norms at work and externally in a social space to mitigate the risk of a second wave. If a population group (or business firm) weighs, or compelled to weigh, economic risk more heavily than the Covid-19 uncertainties, it is likely that enforcement of social norms becomes difficult, and economic revival in the mid-term also suffers. Following Frank Knight’s distinction between risk and uncertainty, for such groups, limited financial choices pose a risk, while being infected and suffer extreme consequences present an uncertainty, and therefore behavioural biases and economic necessities may nudge a shift towards risk-taking to mitigate economic challenges.

3.1 Emerging Debates and Perspectives

Before taking a broad look at the likely organizational challenges, choices and behaviours, it may be useful to look at few high-level trends. In its’ recent coverage, Economist noted[6] three main trends that would get accelerated: De-globalisation; rise of data- enabled services, and consolidation of power into the hands of giant firms. It argued that small and big firms are particularly exposed to the crisis. Bill Gates[7] noted that the “basic principle should be to allow activities that have a large benefit to the economy or human welfare but pose a small risk of infection”, but also noted that “…the picture gets quickly complicated…The modern economy is far too complex and inter-connected for that”. Another discussion[8] (HBR podcast: after hours) looked at three patterns: Trends that will get accelerated (e.g., telemedicine; online education; home working), trends which may get reversed (e.g., shared economy) and trends which will get more complicated (e.g., restaurants). This discussion suggests that there will be three types of firms: Firms, which have strong balance-sheets and will buy assets on the cheap including acquisitions; firms, particularly small and mid-size, which may not have resources to sustain the crisis; and then few smart firms, which have resources, and wanted to make changes for some time and innovate. The slowing-down gives them the space needed. There are also likely to be “mini innovations”, particularly in the service sector, around mitigating Covis-19 risks whilst dealing with public, and firms may advertise them to differentiate their services.

4.0 Strategic Choices and Business Behaviours as “Problem-Solving”

This paper attempts to analyse strategic choices and business behaviours by taking firm as a unit of analysis. It proposes a framework that identifies different markets using nature of demand, and value-chain complexity as two dimensions that could influence firms’ likely behaviours. Industries with products and services that have a high socio-economic impact in the near term get prioritised in the lockdown relaxation process. Public experience with this sector will influence their short-term social behaviours and overall attitudes. Value-chain complexity refers to the exposure, need to interact, inter-dependencies and product/service delivery constraints with various segments (including customers) of the value-chain. In few contexts, it could also serve as a proxy of how easy it is to implement social distance and safety related behaviour norms. Using “high/immediate” and “low/deferred” values for these two dimensions gives four “ideal type” contexts (Table 1) along which business behaviour can be analysed.

4.1 Nature of Demand (Economic Effect)

Classical economics usually classifies demand based on type of industry (consumer and industrial), discretionary income (essential and conspicuous), price-sensitivity (elastic and inelastic), nature of production and consumption (products and services), and sector of economy (primary and secondary). A key influence on economic and business behaviour in the Covid-19 and post-lockdown scenario is the extent to which the existing economic and social equilibrium is impacted (in the near term), when the production and consumption of a particular good or service is deferred. It is hypothesized that if the effect is more (i.e., failure to meet demand could impact socio-economic equilibrium), then businesses may have relatively fewer demand constraints, but will need good management to overcome supply constraints depending on how networked and fragile the eco-system is post-Covid 19. Industries catering to staple goods and essential supplies (like medicines and utilities) fall in this category. If the impact is less ((i.e., demand or supply could be deferred with less immediate consequences), then businesses may face a demand constraint as consumption depends on discretionary income levels and could be deferred at least in the short-term. Capital goods, external entertainment, tourism, and home-design/decoration services are few such examples.

4.2 Value-Chain Complexity

Value-chain complexity refers to the extent to which products and services are dependent, or exposed to, the other elements of the value-chain including customers for meeting the required need. Value-chain could be linear, as in case of a typical supply chain, or it could have pooled inter-dependencies, as in case of public transport or construction projects. If there are limited elements in value-chain or the value-chain is linear and local, then it is relatively low in complexity. Examples could include personal training, legal advisory, and simple retail businesses. If the value-chain resembles a dense network of people and activities, which influence and get influenced by each other, it is a case of high value-chain complexity. Examples include infrastructure projects, hospitals and air travel.

4.3 Strategic Choice and Business Behaviour Framework

The juxtaposition of high and low (in case of value-chain complexity) and immediate and deferred (in case of nature of demand) values give a framework with four business “ideal types”. These categories are named using four types of land resources that provide different types of socio-economic utility, and differ in terms of management choices and behaviours that they engender. Coincidentally, they also invoke the imagery of different social norms that prevail in them. The categories are named as follows:

- Field-Land (Immediate socio-economic effect; low value-chain complexity),

- City-Garden (Immediate socio-economic effect; high value-chain complexity),

- Local Park (Deferred socio-economic effect; low value-chain complexity),

- Forest (Deferred socio-economic effect; high value-chain complexity),

The high and low (in case of value-chain complexity), and immediate and deferred (in case of nature of demand) values represent the high and low points on the spectrum, and in real-life, demand (or value-chain complexity) could fall along any point on the spectrum. Businesses within each box also differ from each other in terms of how “high” or “low” they are from each other, i.e., they could lie at different points on the spectrum even though they are in the same box. In addition, firms within the same industry could fall in different boxes, if their product and services are very different (e.g., emergency medicine as opposed to elective surgery) or their business models entail different types of value-chain complexity (residential schools as opposed to on-line courses). Finally, as Weick[9] noted organizations also enact their environments, and Child[10] pointed out at the role of strategic choice. Thus, it is likely that a firm may not have high value-chain complexity, but functions and makes choices as if it has. In such case, firm could be either over- or under-optimized in relation to the choices it has.

For each of the four categories, a dominant strategic focus is identified from a set of 4Es (Efficiency, Effectiveness, Experimentation, and Exploration). This dominant strategic focus is not prescriptive, and does not preclude the simultaneous pursuit of other focus areas. The strategic focus for each of the four categories is suggestive in nature based on the constraints presented by the nature of demand and value-chain complexity. As an example, if the demand is not a constraint, and supply is not constrained either, the firm would like to focus on efficiency. On the other hand, if supply is constrained (due to Covid-19 risk management and/or value-chain complexity) and demand already exists, then firm will attempt to be effective to overcome the constraints through use of “mini innovations” and smart management processes. It is likely that firms may pursue a combination of 4Es, as they navigate their environments and implement their strategies. Their likelihood of success is greater, if their dominant strategic focus is also the right one suited to their unique context. Differences between the matrix in Table 1 and other strategic models, such as BCG matrix and GE matrix – popular in early days of strategic planning – are covered in the last section of this paper.

The matrix below is a generalized framework, and specifics could differ from firm to firm in any given category depending on context, strategy, leadership values and firm’s culture. This matrix is only a map, and as is commonly noted in philosophy, a map is not a territory.

Table 1: Repertoire of Strategic Choices and Business Behaviours in Different Contexts

4.3.1 Category Type: Field Land (Strategic Focus: Efficiency)

Field Land category consists of firms that supply products and services that are important to public in short-term, and the demand does not vary significantly, unless there is a disruption or seasonal requirement. Such firms supply essential products and services, and in the Covid-19 context, they were largely in operation even during the lock-down. Food supplies, utilities, and critical medical fall in this category. Given the nature of demand, it is largely business as usual, except that there are few additional challenges during the opening of lock-down, such as backlog of demand and services and re-alignment of services (e.g., hospitals postponed elective medical procedures).

In general terms, this sector was already “open” during lock-downs, and therefore the challenges are more likely around how to behave “normal” when everything around is not so normal. In few industries, such as consumable consumer products, may actually see a normal “dip” in demand, because of stock-piling by consumers, but this is likely to be off-set by depleting supply-chain inventory.

Challenges and Choices

Since firms in this category have low value-chain complexity and least demand constraints, their strategic focus is likely to be on “efficiency”, which in turn will be a function of employee performance and supply-chain continuity. A key organizational challenge, therefore, will be around work-force planning and employee engagement and ensuring production goals and work-force priorities are aligned. How this is achieved is likely to be a function of leadership and culture. Firms may choose to be fair, transparent and compassionate; or they may choose to use this opportunity to adopt a short-term approach and “extract” maximum from the employees, whether in terms of output, or revision of pay packages.

Another key organizational challenge will be to ensure that supply chains remain functional and reliable. Though the firms in this category remained open, it is likely that the upstream and downstream supply chains are strained, depleted their own resources and inventories, and therefore the main supply chain could get disrupted. If extensive lock-down exists for long and supply chains are long, this could lead to calls for higher localisation to reduce uncertainty in supply chain. Small suppliers are likely to look for support or reassurances from their partners.

Business leaders will have to make an important choice on how these relationships are framed, two main choices as being opportunistic or collaborative. If business (and employee) relationships are framed as competitive, and leaders prefer “value-extractions” (as opposed to value-creation), then it will have further implications in terms of short-term organizational and social behaviours. Such organizations will value competitive, hard negotiations, and short-term successes.

An important public policy consideration is that while the smooth functioning of this category is essential for consumers, it is unlikely to give a boost to a general economic revival and growth in a significant way. If large sections of populations experience loss of income because of job losses and economic slow-down, it will also impact firms in this category.

4.3.2 Category Type: City Garden (Strategic Focus: Effectiveness)

Firms in this category have variety in the value-chain and immediate socio-economic effect. Such firms will have high levels of value-chain inter-dependencies and also likely to experience demand once the lock-down is softened. Elective medical surgeries and local public transport are two such examples. Other examples include ancillary industries, financial services and residential education. Such firms are likely to have high demand in part because of backlog. They also likely to experience the constraints of social-distancing more severely, because the value-chain involves high inter-dependencies, which could be a proxy, in certain cases, for social interdependencies, as in medical and transport. It is likely that these sectors are opened cautiously and demonstrate a “slow motion” economic behaviour.

Challenges and Choices

Firms in this category are likely to have no shortage of challenges. Unlike “Field Land” firms, “City Garden” firms will be “opening” up operations after the lock-down, or making the transitions from offering limited and essential operations to full operations. Key strategic focus for these firms will be on effectiveness, as their operations will take place in a context of social-distancing rules, which will have an impact on efficiency and volume. Firms in this category will need to be smart about management, adopt new processes and adapt to new social norms, so that they can able to do maximise effectiveness (managing risks and social distancing norms) to do more business.

Firms in this category will be under pressure to “recover” the lost business during lock-down through “high price”, “high volume” (limited by the Covid-19 social distancing and risk management measures) or with changes in the business model. This will however not be a normal demand and supply economics for firms, as Covid-19 risk management processes and the social distancing may lead to exogenous, or “artificial” supply constraints for the consumers, and “artificial” demand constraints for the producers. Firms will face decision, such as deciding on the criteria on which to “ration” their services; who and how to assess the “need” of consumers; and the “price” to charge. If enough firms follow dynamic pricing to decide on the allocation of services, it is likely that the demand will become elastic and prices will get re-set at the equilibrium after few “price” shocks. This is, however, unlikely to happen in contexts with high population and a critical mass of demand at most price points.

Another organizational challenge for such firms will be to speedily and effectively adapt internal processes, so that they can comply with social-distancing other behavioural norms, and within that constraint maximise the business volume. Like other situations, the role of leadership will be important. Firms may or may not enforce the norms strictly to maximise volume and risk public health safety and reputation, or they could use smart thinking and “mini” innovations through process improvements, use of IT as well as work force strategies. Since the constraints here are interactions and network instead of demand itself, management practices and innovations that work around these constraints will give a temporary advantage to firms. This could also lead to firms discovering best practices for future as well. Firm could also innovatively build demand, which is lost because of growing anxieties on Covid-19 risks. For example, service provides in a shared economy or a service business could differentiate by adding product/service features that address the concern and provide peace of mind.

Leadership, culture and employee engagement are likely to be a crucial for another reason. Staff on the front-lines will be crucial in how public experiences the health risk constraints, their unique situations are accommodated, and social norms are enforced. Being on the ground dealing with public directly, frontline staff will be in pivotal position to maximise business through maximisation of customers’ experience and safety measures, and build strategic advantages.

Getting the human resources part right will be an important challenge. Workforce planning will involve difficult trade-offs, such as employees being keen to come back to work, but work-force planning or business volume limits that possibility; or there may be employees, who the firm wants back due to their skill-set, but whose situation and risk perceptions do not allow that. It will involve questions, such as whether they have legal rights to not come back, and if yes, what are pay and career implications for them. It is also likely that human resources issues are increasingly looked through cost perspective, and salary freezes, manpower cuts and business model re-alignments are actively considered. Business leaders will have a choice in terms of deciding whether the employee costs will be the first cost item to cut, or to wait out until it is unavoidable, and perhaps more importantly, the method and process to use, whilst making such decisions.

Another major organizational challenge in this category is likely to be with respect to uncertainty and risk management posed by the inter-dependencies in the value-chain. This covers both the Covid-19 risks as well as uncertainties with respect to demand and supply of inputs/outputs. Though the practices followed by essential consumer supplies and super-markets during lock-down could provide comfort in the ability to manage, the inter-dependencies there were mostly linear in nature. Firms in “City Garden” category mostly are characterized by pooled and networked interdependencies. Leadership, however, may have a choice. They could develop strategic (and collaborative) partnerships where crucial inter-dependencies exist, or could engage opportunistically and transnationally with the suppliers and employees. In terms of business strategy, firms may choose to either co-opt the uncertainties through business alliances, acquire firms, or even align their business models, at least temporarily, with the emerging normal.

Main organizational challenges will involve building effectiveness by designing smart management processes using employees, organizational capabilities and technology, so that business volume can be optimised (or maximised) safely. Leadership challenges will involve addressing human resources challenges in a fair and transparent way, and building trust and culture. Employees will hold the key to how management processes are leveraged to business advantage. Organizations may also have to re-assess the uncertainties in their value-chain and eco-systems, align business-models temporarily, and build organizational capabilities, which were outsourced previously for cost reasons, but pose strategic uncertainties now.

4.3.3 Category Type: Local Park (Strategic Focus: Experimentation)

This category consists of firms, which are likely to experience low demand (or low changes in demand pre- and post-lockdown), but also have low levels of interdependencies in the value-chain. Such products and services will largely involve industries that offer individualised experiences (such as publishing), specialist or bespoke services (taxation, home design, legal work, etc), specialized process industries and online education. Firms in this category are likely to be niche or specialist firms, mostly small to mid-size, but could include large firms as well.

At a high level, it seems that firms in this category are likely to be relatively less impacted, except that an economic slowdown slows down all economic activities and impacts discretionary spends all round the economy. This will be the case for firms in this category, which depend on discretionary incomes and savings, such as home design, or investing in self-development. Industries in this category, which have price elastic demand curves, therefore, may face price competition and lower margins, and may have to compete on price or product/service differentiation.

Challenges and Choices

Given the largely non-essential nature of demand, an important challenge for firms in this category will be to de-couple their business prospects with the general economic cycle in the short run. This suggests that their strategic focus could be on experimentation. Due to low interdependencies and complexity in the value-chain, few firms in this category may have the space and option to scale-up businesses up to a point using technologies. Tele-medicine and on-line education are examples of such businesses. Other businesses may choose to use price-cutting as a strategy, or providing additional value for a given price. Firms could also experiment with the business equivalent of “stock option”, wherein clients can buy services at a given price at a future date by paying part of cost now. Other firms could take an advantage of slow-down to build their own capabilities in related areas to diversify in the near future. Activities, such as physical training, industrial consulting, and legal advisory follow in this category. Firms in this category could also use the slowing down to solidify their relationships and understanding customers better, build their own management processes, and also do experimentation either in terms of service variations or business models.

Firms in this category could look at scaling-up as a strategic option as well as experiment broadly, understand and develop customer relationships, and re-frame their business approach to value-creation as opposed to value-extractions from their customers.

4.3.4 Category Type: Forest (Strategic Focus: Explorations)

Firms in this category have high complexity in their value-chains and the consumption of their products and services can be deferred in the short term by the consumers. In general, products and services offered by firms in this category do not make a difference to a consumer from one day to another, but potentially yield gains in the long run. Industrial products, construction, and infrastructure fall in this activity. These sectors are sensitive to economic uncertainty and result in low investments in times like this. Generally speaking, economic policy and government investments have a large role to play in this sector.

Challenges and Choices

Since the need for such products is not essential in short run, firms in this category may experience uncertain future in the near future, though it depends on the context and nature of product. Firms that provide supplies to utilities could experience less slow-down than firms that undertake road or building construction. Firms in this category were experiencing a slow-down even before the Covid-19 crisis, but the lockdown and recession made the future for such firms worse. Equally importantly, pre-Covid-19 crisis, firms in these sectors were also experiencing significant industry changes due to advent of new technologies (such as Internet of Things; automated manufacturing; and robotics). Other firms in this category, such as power sector, were going through business shifts led by advancement in renewable energies, micro-power generation, and smart distributions. Construction sector was going through recession partly, because of rise of shared economy in hospitality industry (say, Airbnb) and commercial rental (say, WeWork).

An important challenge for firms in this category in the short run is lack of demand, though in few cases there may be small window of activity to complete the projects, which were in progress, before the lockdown started. In the long run, the problems for the firms in “forest” category cover both strategy and human resources challenges, as demand is unlikely to revive soon. The strategic focus for such firms is likely to be on exploration. The strategic options to explore range from re-alignment of business model towards segments, which are likely to be in demand first; strategic divestments; pivot towards new trends and opportunities, which earlier seemed risky and not financially attractive (such as renewable energy or industrial automation); strategic acquisitions and new business partnerships which align well the future strategy; identifying gaps in the regional or local industrial eco-system due to de-globalisation and a desire to build “cushion” in the infrastructure; and building new organizational capabilities. The building of localised industrial eco-systems, acquisitions, and support for new technologies, such as renewable energies, however, will be influenced by public policy outlook and general business attitudes.

These strategy options, however, will take time to develop into revenue streams for the businesses. In the short run, main challenge will be survival and dealing with human resources related issues. This could mean cost rationalization as well as decisions on headcount. As in previous categories, while firms can adopt a short-term transactions approach in HR matters, part of the value created by firms in this category depends on the specialized skills and relationships. It is not unlikely that the secondary effects of Covid-19 crisis continue with varying levels of severity in different regions and countries, and trend towards local industries become mainstream. If this happens, demand in this sector may revive in the mid-term and a firm with strong human capital will be ideally suited to influence this shift and create value.

5.0 Differences from Existing Strategic Matrices/Models

It is perhaps useful to note the differences between the strategic models (such as BCG matrix and GE matrix), which also addressed strategic choices for firms under different scenarios, and the conceptualisation proposed in this paper. Strategic models, of which BCG and GE matrix were two well-known examples, were common as planning tools in the US in the early days of strategic planning and later. These were, in general, business planning and resource allocation tools based on industry/market attractiveness and business strengths. There have been developments in strategy field both at research and practice levels, which made the field richer and also more nuanced. Michael Porter[11] (Industrial Economics), Richard Rumelt[12] (Resources-based view), C.K. Prahalad and Gary Hamel[13] (Core Competence), and Christopher Bartlett and Sumantra Ghoshal[14] (Organizational Purpose) and others provided different perspectives in the field of strategy. At the practice level, businesses and economies have become highly inter-connected and network based, business models have proliferated, market and industry boundaries have become more fuzzy, globalisation and technology has introduced an uncertainty where industry attractiveness and business strengths are less enduring that they used to be, and firms themselves have become more complex. The situation post lockdown, which is subject matter of this article, has become even more complex, because social and Covid-19 uncertainties have made markets and economy a kind of dancing landscape. This model differs from previous models in two respects: It uses value-chain complexity (also a proxy of business and social distancing risks) and nature of demand that could impact socio-economic equilibrium as an important influence on strategic and internal choices – it is therefore not about market and business, but about how they interact together in an uncertain context; and it emphasises the important role of business leadership in approach towards human resources, trust building and building internal management processes as elements of strategic focus.

End Notes

[1] Schön, Donald A as cited in Sood, Anil. Building Critical and Reflective Thinking Capability. https://www.ideassansideology.org/building-critical-and-reflective-thinking-capability/

[2] Ibid

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid

[5] Smith, Jake J. Contaning COVID-19 Will Devastate the Economy. Here’s the Economic Case for Why It’s Still Our Best Option. March 26, 2020. Based on the Redearch of Martin Eichenbaum, Sergio Rebelo and Mathias Trabandt. https://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/economic-cost-coronavirus-recession-covid-deaths

[6] “The business of survival” The Economist, April 11, 2020, pp.7

[7] Gates, Bill. The first modern pandemic. The scientific advances we need to stop COVID-19. April23, 2020.

[8] “Predictions for the New Normal I HBR Presents after hours” HBR Podcast. 30.01 minutes. 15th April 2020.

[9] Weick, K. E. (1979). The social psychology of organizing. (2nd ed.) Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

[10] Child, John. (1972). Organizational Structure, Environment and Performance: The Role of Strategic Choice. Sociology-the Journal of The British Sociological Association – SOCIOLOGY. 6. 1-22. 10.1177/003803857200600101.

[11] Porter, M.E.(1980) Competitive Strategy. Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. The Free press, New York, USA.

And

Porter, M.E.(1985) Competitive Advantage. Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. The Free press, New York, USA.

[12] Rumelt, R.P. (1984). Towards a strategic theory of the firm. In R. Lamb (Ed.), Competitive Strategic Management, 556-570. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

[13] Prahalad, C.K. & Hamel, Gary. (1990). The Core Competence of the Corporation. Harvard business review. 68. 79-91. 10.1016/B978-0-7506-7088-3.50006-1.

[14] Bartlett, Christopher A., and Ghoshal, Sumantra. 1994. “Changing the Role of Top Management: Beyond Strategy to Purpose.” Harvard Business Review (November – December): 79 – 88.

It is an interesting and highly informative article. Same framework can also be used for different products produced by a firm.

Thank you for reading the article and comments. I agree that the same framework can be used for different products produced by a firm. This can also be done at the industry level.

In fact, I am currently trying to see its application into the banking industry, which is a complex ecosystem with different business models, sizes, strategies, ownership types, governance requirements, and regional/geographic scope. Could there be any patterns (or differences) in approaches and strategies depending on business models, sizes, geographical area, etc? The last point (geographical area) is important, because Covid-19 also has a geographical dimension. At different points in time, different countries, regions and cities experience varying levels of severity, customer and economic impact.

I appreciate your feedback and any further ideas you may have.

Thanks,

Anujayesh