Building Critical and Reflective Thinking Capability

Learning and reasoning are among the two most important contributors to the evolution of human society. We learn and reason often consciously, but many a times unconsciously and sub-consciously. Our choices and action are often guided by what we know and what we want to know.

In this paper, I have made an effort to put together a summary of literature on critical thinking, reflective thinking and reflective practice. While there are many good review papers on critical thinking[1][2][3], I have not been able to locate many papers that explores the relationship between critical and reflective thinking and reflective practice[4].

As a first step, I have provided a short summary of philosophical, psychological and education perspective on critical thinking and then attempted to present an integrated view. As for reflective thinking and reflective practice, I have drawn upon John Dewey and Donald Schön’s work, who have probably been the most influential contributors in the field.

The first two sections of the paper outline what my motivation is and how I see the need for learning through critical and reflective thinking and reflective practice. Section III to V serve as the summary of literature on critical thinking, summary of Dewey’s ideas on reflective thinking and that of Schön on reflective practice, respectively. Section VI discusses the role of mental models in reflective thinking and practice and the final section puts together an approach, built around a set of questions, which can help us enhance our critical and reflective thinking and reflective practice capability.

Learning to Reflect: Insights of a Teacher and a Practitioner

As a teacher, I have a natural interest in understanding how we learn and what I can do to help everyone learn. Since a large part of my experience is in the context of executive education, I have been interested in discovering how learning (education) transforms into action and benefits individuals and organisations. I recall a couple of my earliest conversations with two senior human resource professionals who asked me the following:

- We know that your institute has a great reputation for teaching the public sector, but how would you teach us in the private sector?

- We spend a lot of effort and cash in training our people but how can you help improve business results, leveraging the knowledge you are sharing?

My inferences from these questions were that people working in the public sector learn differently from those in the private sector and it needs effort to apply knowledge to real-life situations and deliver results. My response to both these situations was that I must learn well about the business and people, if I have to contribute to their learning and help them deliver business results. Consequently, I started using context-specific exercises and cases, decision-simulations and action-learning projects in my teaching.

A few years later, I had another question come up for me, this time from a senior finance professional – can you teach a course on problem-solving to our finance team? I was already teaching a course on Business Analytics for the finance team and my view was that if we analyse a situation well, we can solve the problem too and we don’t need a course on problem-solving. But the finance leader did not see it that way. This conversation took me back to an experience during my early days in industry as a young professional, straight out of a business school.

“I was presenting an expenditure analysis (the usual budget versus actual) to my then Vice-President Finance, detailing the usual price-volume-mix variance.

He asked me – what has caused such a large variance?

My response was – volume.

But what his question was – what has caused the volume to vary so much?

I had no clue!

The expenditure head, we were discussing, was the amount of subsidy we were providing to the local farming community who were supplying us fresh milk for processing. In this particular year, we were facing a severe drought and green cattle-feed production in the area had fallen significantly.

We, as the major buyer of fresh milk in the area, decided to procure processed feed (outside the state) and provide larger quantities at subsidised prices to the community.

That was the cause, indeed!”

This incident was an eye-opener for a young professional in me, but it was part of my Vice-President’s knowledge base. The lesson for me was that volume is not the cause, the cause was the drought conditions and the choice we made to provide processed feed at subsidised rates so that the cattle is taken care of and our milk procurement during the next season can come back to the normal levels.

I have also had the experience of teaching finance to the same set of professionals, over a decade, of a large company as part of their leadership development programmes. As a professional’s responsibility moved to the next level of leadership role, he or she would attend the next stage of leadership development programme and I would be there to teach finance. During many informal conversations, I had people tell me that they don’t remember much from the previous class as they did not have an opportunity to apply what they had learnt about finance in my earlier class.

All the questions and the experiences helped me realise the following:

- Not everyone learns the same way.

- It is not easy to apply even when you know a subject.

- It is not enough to learn in the classroom, if we want to internalise our learning. We must apply. In other words, application is an effective way of learning.

- We must have a good understanding of a situation before we recommend or makes choices and allocate resources, particularly the factors that impact our choices and the result of our actions.

It is these experiences and insights that brought me to formal literature on problem-solving to start with, then to learning in education and critical thinking and finally to reflective practice, reflective thinking and mental models. The present paper, therefore, is my early effort at contributing to an extremely well-research field.

In the next section, I have articulated the need for critical and reflective thinking led-practice in 21st century.

Learning Needs of a Knowledge-Society

Philosophers and education theorists have included cultivation of curiosity, disposition to enquire, development of sound judgment, fostering of autonomy and fostering of skills and dispositions constitutive of rationality or critical thinking as the purpose of education.[5] Yet we observe that many of us tend to take information and other stimuli at their face value and respond immediately, resulting in an error of judgment or accepting arguments that may or may not have been tested for objectivity.

At a time, when we are receiving or have access to a large amount of information through multiple sources, we run the risk of creating a make-belief world around ourselves. Halpern argues that the ‘ability to know how to learn and how to think’ will be the most desirable education for the 21st century.[6] The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has identified critical thinking as the 21st century skill.

While we have experienced an unprecedented level of economic growth across many regions in the world since the mid-eighties to the early part of this century, we still have a significant part of humanity living in poor physical, social and economic conditions. The ‘great recession’ caused by the financial crisis has resulted in the hundreds of millions of people in the developed as well as the developing world facing an uncertain future.

At the same time, we are at a stage of development where there is no dearth of opportunities to do better. The developed world requires to create meaningful economic opportunities for its young population in a low-growth environment where introduction of technology is resulting in a fast-paced reduction in number of traditional job openings. The emerging world needs to create millions of new economic opportunities for its young in an environment where there is a need for considerable reduction in resource-intensity of economic activity.

We need to reduce energy and water intensity of economic activity. At the same time, globalisation of economic activity has resulted in increasing the degree of competition for resources as well as the share of consumer’s wallet. Consequently, the key success factors for 21st century are not expected to be the same as in the 20th century, when global access to resources and technology was limited, information and media technology revolution was at early stages, mass media was not yet global and global travel was not as accessible as it is now.

The recent developments in robotics, artificial intelligence, 3-D printing and sensor technology, combined with advances in computing power, are expected to result in the work being done very differently in the coming few years than it is at present. We expect that an increasing amount of physical work will start getting done by machines. In other words, we no longer live in a world where the physical effort, combined with limited education, will help an individual earn enough for providing a reasonable living for a family.[7]

In order to evolve from the physical-effort based economic activity to knowledge-based economic activity, we will need individuals with very different capabilities – the ability to think critically and learn to think and practice under complex, unfamiliar situations.

In what follows, I discuss the idea of critical and reflective thinking and reflective practice as it has evolved and present an integrated view bringing together philosophical, psychological and education perspectives on what critical and reflective thinking means. As a next step, I have explored the question how to enhance our capability for reflective practice.

Critical Thinking

Susan Fischer mentions that the issue of critical thinking (CT) capability as key to reflective practice has primarily concerned philosophers and educators, which is not surprising as thinking is the primary activity for a philosopher and building thinking capability is the primary activity for an educator.[8] Consequently, the construct development has largely been based on philosophical arguments and not on empirical findings. It is not at all surprising that the critical thinking idea has evolved from philosophy and education, given that the idea itself owes its existence to Socrates, Plato and Aristotle who placed reasoning at the centre of education, with an objective of fostering good judgment and wisdom.[9] Fischer also mentions about the multiplicity of definitions with many different themes.

In philosophy, the idea of critical thinking has evolved as an ideal type. In other words, it is built around the disposition of a thinker – disposition that allows a person to engage in and encourage others to engage in critical judgments. The American Philosophical Association (APA) has arrived at a consensus disposition of an ideal critical thinker.[10] Table 1 below lists the characteristics of an ideal critical thinker’s disposition in two broad groups – characteristics that reflect a person’s attitude towards self and others in the society in specific as well as general life-situations.

Table 1 Dispositions of a Good Critical Thinker

| Approach to Life and Living in General | Approach to Specific Issues, Questions or Problems |

| Inquisitiveness with regard to a wide range of issues | Clarity in stating the question or concern |

| Concern to become and remain well-informed | Orderliness in working with complexity |

| Alertness to opportunities to use critical thinking | Diligence in seeking relevant information |

| Trust in the processes of reasoned inquiry | Reasonableness in selecting and applying criteria |

| Self-confidence in one’s own abilities to reason | Care in focusing attention on the concern on hand |

| Open-mindedness regarding divergent world views | Persistence though difficulties are encountered |

| Flexibility in considering alternatives and opinions | Precision to the degree permitted by the subject and the circumstance |

| Understanding of the opinions of other people | |

| Fair-mindedness in appraising reasoning | |

| Honesty in facing one’s own biases, prejudices, stereotypes, or egocentric tendencies | |

| Prudence in suspending, making or altering judgments | |

| Willingness to reconsider and revise views where honest reflection suggests that change is warranted. |

Given the disposition of an ideal critical thinker, APA has outlined the cognitive skills that are central or core to development of critical thinking capability.

Table 2: Cognitive Skills and Sub-Skills required for Critical Thinking

| Skills | Description | Sub-Skills |

| Interpretation | To comprehend and express the meaning or significance of a wide variety of experiences, situations, data, events, judgments, conventions and beliefs, rules, procedures or criteria. | Categorisation, Decoding Significance, Clarifying Meaning |

| Analysis | To identify the intended and actual inferential relationships among statements, questions, concepts, descriptions or other forms of representation intended to express beliefs, judgments, experiences, reasons, information or opinions. | Examining Ideas, Detecting Arguments, Analysing Arguments |

| Evaluation | To assess the credibility of statements or other representations which are accounts or descriptions of a person’s perception, experience, situation, judgment, belief or opinion; and to assess the logical strength of the actual or intended inferential relationships among statements, descriptions questions or other forms of representations. | Assessing Claims, Assessing Arguments |

| Inference | To identify and secure elements needed to draw reasonable conclusions; to form conjectures and hypotheses; to consider relevant information and to deduce the consequences flowing from data, statements principles, evidence, judgments, beliefs, opinions, concepts, descriptions, questions or other forms of representations. | Querying Evidence, Conjecturing Alternatives, Drawing Conclusions |

| Explanation | To state the results of one’s reasoning; to justify that reasoning in terms of evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological and contextual considerations upon which one’s results are based; and to present one’s reasoning in the form of cogent arguments. | Stating Results, Justifying Procedures, Presenting Arguments |

| Self-Regulation | Self-consciously to monitor one’s cognitive activities, the elements used in these activities, and the results educed, particularly by applying skills in analysis and evaluation to one’s own inferential judgments with a view towards questioning, confirming, validating or correcting either one’s reasoning or one’s results. | Self-Examination, Self-Correction |

Considering the idea of an ideal thinker and the required cognitive skills, APA defines critical thinking to be “… purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based.”

I argue that self-regulation be seen an over-arching skill that helps distinguish between critical and non-critical way of interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference and explanation. In other words, an individual willing to examine and correct him or herself is expected to interpret and analyse a situation more comprehensively and critically than a person who does not self-examine or self-correct. Therefore, I see self-regulation as a disposition rather than a cognitive skill.

Philosophical perspective also includes the quality of thought as an additional dimension to be explored.[11] The APA experts involved in preparing the consensus statement argue that it is not enough to be adept at skills, one must habitually apply them appropriately. They argue that a good critical thinker has these skills and certain valuable habits. The consensus statement on teaching and accessing critical thinking skills highlights the following aspect:

“Reflecting on and improving one’s CT skills involves judging when one is not performing well, or as well as possible, and considering ways of improving one’s performance. Learning CT involves acquiring the ability to make such self-reflective judgments.”

The above-mentioned APA statement in a way supports my assertion that self-regulation be seen as a disposition rather than a cognitive skill, as it hints at self-regulation being the basis for determining whether one is thinking critically or not.

Elder and Paul[12] mention the following to be the criteria for assessing the quality of thought:

Table 3: Criteria for Assessment of Quality of Thought

| Criteria | Description |

| Clarity | Clarity is the gateway standard. If a statement is unclear, we cannot determine its accuracy or relevance. In fact, we cannot say anything, as we don’t know what it is saying. |

| Accuracy | A statement can be clear but not accurate. |

| Precision | A statement can be both clear and accurate, but not precise. |

| Relevance | A statement can be clear, accurate and precise, but not relevant to the question at issue. |

| Depth | A statement can be clear, accurate, precise and relevant, but superficial, i.e., lack depth. |

| Breadth | A line of reasoning may be clear accurate, precise, relevant and deep, but lack breadth. |

| Logic | When we think, we bring a variety of thoughts together into some order. When the combination of thoughts is mutually supporting and makes sense, the thinking is “logical.” If it is not mutually supporting or does not “make sense,” it is not logical. |

| Fairness | Our thinking is often biased in the direction of the thinker – towards the perceived interests of the thinker. We do not naturally consider the rights and needs of others on the same plane as own rights and needs. We therefore must actively work to ensure that we are applying the intellectual standard of fairness to our thinking. Since we naturally see ourselves as fair even when we are unfair, this can be very difficult. A commitment to fairmindedness is a starting place. |

The cognitive psychology literature defines critical thinking in terms of cognitive skills and processes used by a critical thinker, i.e., types of actions or behaviours critical thinker do or demonstrate. Sternberg defines it to be “the mental processes, strategies and representations people use to solve problems, make decisions, and learn new concepts”. [13] Diane Halpern has also defined critical thinking on similar lines and she sees it as “the use of those cognitive skills or strategies that increase the probability of a desirable outcome”.[14]

While the cognitive psychology view evolves from a psychologist’s need to define constructs in way that they can be directly observed, Sears and Parsons see critical thinking as a ‘way of living in and addressing the world’ and not just a useful teaching strategy.[15] They articulate the following seven principles underlying an Ethic of Critical Thinking:

- Critical thinking requires the attitude that knowledge if not fixed but always subject to re-examination and change

- Critical thinking requires the attitude that there is no question which cannot or should not be asked

- Critical thinking requires an awareness of and an empathy for alternative world views

- Critical thinking requires a tolerance for ambiguity

- Critical thinking requires an appreciation for alternative ways of knowing

- Critical thinking requires a sceptical attitude towards text

- Critical thinking requires a sense of the complexity of human issues

Halpern identifies the following critical thinking dispositions and skills:

Table 4: Halpern’s List of Dispositions and Cognitive Skills

| Dispositions | Cognitive Skills |

| Willingness to engage in and persist at a complex task | Verbal Reasoning Skills, needed to comprehend and defend against the persuasive techniques that are embedded in everyday language. |

| Habitual use of plans and the suppression of impulsive activity | Argument Analysis Skills, allowing us to establish relationship between reason and conclusion, identify stated or unstated assumptions and identify irrelevant information and ideas. |

| Flexibility and open-mindedness | Hypothesis Testing, being able to choose the right sample size, test validity, assess reliably and accurately and move from particular to general. |

| Willingness to abandon non-productive strategies in attempt to self-correct[16] | Likelihood and Uncertainty, being able to use cumulative, exclusive and contingent probabilities correctly |

| An awareness of the social realities that need to be overcome, e.g., the need to seek consensus or compromise | Decision-Making and Problem Solving, with particular focus on generating and selecting alternatives and judging |

I see no conflict between Halpern and APA’s list of dispositions and cognitive skills required for critical thinking. Both list argument analysis as one of the cognitive skills and I see verbal reasoning skill as a way to comprehend, interpret and explain. Similarly, hypothesis testing is one of the ways to analyse and evaluate.

I don’t see problem-solving and decision making (Table 4) as the cognitive skills, unlike Halpern, Sternberg and many other researchers. I see them as situations where we apply our critical thinking capability.

We would also like to clarify that the list of activities and steps involved in the problem-solving process, as listed by many approaches to problem-solving, are not to be seen as the skills required for critical thinking. For example, some of the approaches list evaluation of alternatives as one of the steps, which is different from evaluation as the cognitive skill. Evaluation of alternatives is just one application of the skill of evaluation.

I also don’t see any major difference in the idea of habitual application of skills and dispositions as proposed by the two schools of thought. Disposition is nothing but the state in which a person demonstrates conscious competence.[17] Sears and Parsons’ idea of Ethic of Critical Thinking is also a pointer towards the seven principles being part of a person’s nature or disposition.

The philosophers argue that we run a risk of becoming focused on activity and the processes (analysis, interpretation, etc.) of completing the activity, if we accept the cognitive psychology view in its entirety.

Bailin argues that critical thinking is essentially a normative concept and therefore it cannot be seen as a set of mental processes or a series of procedural steps. It is the quality of thinking that matters and the quality is determined by the degree to which thinking meets the relevant standards and criteria. The procedures are, at best, heuristics or pointers towards the aspects that need to be studied. Even a diligent application of steps may not necessarily lead to solving a problem or understanding a phenomenon.

I agree with Bailin that critical thinking should not be seen as a mere application of steps, which is really an unthinking way and therefore a degenerate case of application. In other words, I argue that an unthinking application is likely to fail the quality of thought criteria presented in Table 3[18].

Bailin also mentions that the background knowledge in the relevant area is an important determinant of quality of thinking, allowing us to make a reasoned judgment. Given that she sees critical thinking ability as a set of resources (and not as a set of skills and processes), she reframes the issue of generalisability of critical thinking capability across domains as the challenge of applying one’s resources to a particular context. Therefore, the question of generalisability is not really a question to be worried about.

Finally, the educationists’ view of critical thinking is centred on information processing skills. Bloom’s taxonomy of information processing skills is one of the most influential views in this context. He classified cognitive processes into six levels – knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation (lowest to the highest order process). While the education approach is based on years’ of classroom experience, it is not seen as rigorous enough, as the framework evolved from experience has not been tested applying the same principles as in the case of philosophical and psychological approaches.[19] In any case, I see the Bloom’s taxonomy to be part of cognitive skills outlined by philosophy as well as the psychology approaches.

Given all the three perspectives, I see critical thinking to be a way of life that can help us improve the effectiveness of any human endeavour, individually and collectively, resulting in better life experience for all of us. I don’t see the three perspectives to be independent lines of thinking or research. I see them as an integrated whole – one needs the other for ideas to get realised in action.

I see the philosophical view as the foundation for any discussion on critical thinking and psychological view as a way to operationalise the philosophical ideas and assess our progress (as observed in our behaviour) on the development path, using empirical methods including experiments, case studies, action-research, participant-observation and so on. The educationist’s effort is directed at helping all of us develop our critical thinking capability. In other words, we need all the three-perspectives to help us understand what critical thinking is, how it evolves and how we can enhance our ability to think critically.

I also draw upon Dewey’s work where he describes the then prevailing view of psychology being concerned with natural history of thought (i.e., how a particular thought came to be or how it presents itself) and logical theory being concerned with the question of eternal thought and its eternal validity. He draws upon the advance of the evolutionary method in natural science to argue that the distinction between psychology being concerned with natural history of though and logical theory with abstract eternal nature of thought is unsustainable.

Bringing together all the ideas from the three perspectives, I propose the following to be the critical thinking framework:

Figure 1: Critical Thinking Framework

Dewey on Reflective Thinking

Willingness to reconsider and revise views where honest reflection suggests that change is warranted is listed as one of the dispositions that help us realise better life experience in general (Table 1). We consider this to be a characteristic that allows us to learn by stepping back and thinking about our ideas and experiences, an idea close to what Dewey described as reflective thinking.

Dewey describes a reflective thought to be a thought that “comes after something and out of something, and for the sake of something…thinking of every day practical life and of science is of this reflective type. We think about; we reflect over…Reflection busies itself alike with physical nature, the record of social achievement and the endeavours of social aspiration. It is with reference to such affairs that thought is derivative; it is with reference to them that it intervenes or mediates.” (Pp. 1 and 2)[20] In other words, thinking is grounded in our life-experiences.

In Dewey’s world, there is no qualitative difference between the methods of science and that of everyday life. In support of his argument, he mentions the following:

“He assumes uninterrupted, free, and fluid passage from ordinary experience to abstract thinking, from thought to fact, from things to theories and back again. Observation passes into development of hypothesis; deductive methods pass to use in description of the particular; inference passes into action with no sense of difficulty save those found in the particular task in question. The fundamental assumption is continuity in and of experience.” (Ibid. Pp. 10)

Dewey further argues that it is the situation, in which the various factors are actively incompatible with each other, that forms the antecedent for reflective enquiry, a situation that is in conflict with itself where it is not possible to determine what in particular is objective and what can be taken as an organized harmonious whole – complex, fluid situation, a ‘problematic setting’. (Ibid. Pp. 40)

In a very comprehensive set of statements, Dewey argues that “origin of thinking is some perplexity, confusion or doubt…There is something specific which occasions and evokes it…the next step is suggestion of some way out – the formation of some tentative plan or project, the entertaining of some theory which will account for the peculiarities in question, the consideration of some solution for the problem. The data on hand cannot supply the solution; they can only suggest it…If the suggestion that occurs is at once accepted, we have uncritical thinking, the minimum reflection. To turn the thing over in mind, to reflect, means to hunt for additional evidence, for new data, that will develop the suggestion, and will either…bear it out or else make obvious its absurdity and irrelevance. Given a genuine difficulty and a reasonable amount of analogous experience to draw upon, the difference, par excellence, between good and bad thinking is found at this point…Reflective thinking, in short, means judgment suspended during further enquiry…the most important factor in the training of good mental habit consists in acquiring the attitude of suspended conclusion, and in mastering the various methods of searching for new materials to corroborate or to refute the first suggestions that occur.” (Pp. 11-13)[21]

Elsewhere, Dewey argues that an experience arises from the interaction of the principles of continuity (each experience influences future experience) and interaction (situation influences our experience).

He states that “every experience both takes up something from those which have gone before and modifies in some way the quality of those which come after” – thus forming an experiential continuum. (Pp. 35) [22] While discussing the principle of interaction, Dewey mentions the following:

“An experience is always what it is because of a transaction taking place between an individual and what, at the time, constitutes his environment…The two principles of continuity and interactions are not separate from each other. They intercept and unite…the longitudinal and lateral aspects of experience…What he has learned in the way of knowledge and skill in one situation becomes an instrument of understanding and dealing effectively with situations which follow.” (Ibid. Pp. 43-44).

In other words, experiential continuum and the interactions with different situations help build capability for dealing with a range of situations. The process of reflection involves looking back over what has been done so as to extract ‘net meaning’, which is the capital stock for dealing with further experiences. (Ibid. Pp. 87)

Dewey’s idea of ‘net meaning’ or the ‘capital stock’ or ‘knowledge’ is the mental model we all build for dealing with a given situation or situations, the model which helps us develop an intuitive understanding of the situation and broadly know the cause-effect relationships and the impact of our choices and actions on ourselves and on our environment.

Dewey argues that the value of experience be judged by the effect it has on an individual’s present, future and the extent to which one can contribute to our society.

Dewey suggests that learners are aware of and control their learning by actively participating in reflective thinking (assessing what they know, what they need to know, and how they bridge that gap) during learning situations.

Dewey defines the purpose of education as to establish the connection between the achievements of the past and the issues of the present so that we can deal with future more effectively. He describes education to be development from within by observing and reflecting on our own experience. (Ibid. Pp. 27 and 28)

He challenges the teachers to build a theory of experience, which allows us to progressively organise our subject in a way that it takes into account a student’s past experience and then provides them with experience which helps open up, rather than shut down, a person’s access to future growth experience. In this sense, all of us are teachers without formally being called one. At home, children learn from parents’ experience and vice-versa and at work place managers learn from their teams and vice-versa. (Ibid. Pp. 30)

In summary, Dewey sees reflective thinking to involve looking back at our own experience, building a mental model, extracting ‘net meaning’ and being able to make effective choices even in complex and fluid situations. He sees reflective thinking capability as key to building a better society, with the purpose of education being creation of opportunities for purposeful learning.

Donald Schön on Reflective Practice

Building on Dewey’s idea of ‘problematic’ situation, Schön argues that a professional, more often than not, faces an indeterminate swampy zone of practice where the problem cannot be solved by applying theory and technique derived from scientific knowledge.[23] (Pp. 3)

Schön, while discussing the role of professional practice from technical rationality perspective mentions that the professional practice’s emphasis on problem solving ignores ‘problem setting’. Every experience is situated in a physical and social context and therefore the need to understand the situation is as important as the need to choose among available means.

Schön illustrates this point by saying that a civil engineer knows how to a build road suited to the conditions of a particular site and specifications, drawing on his or her knowledge of soil conditions, material and techniques of construction. But the problem of what road to build or whether to build one at all is not solvable by the application of technical knowledge, not even using sophisticated decision theory methods. (Ibid. Pp 4)

Schön argues that there is a tacit knowledge (professional artistry) involved even in situations where we can depend on scientific knowledge (how to build a road), which gets revealed in our intelligent action – publicly observable physical performance. He refers to such know-how as knowing-in-action – spontaneous skillful execution. (Ibid. Pp. 21 to 25)

On the other hand, an indeterminate situation[24] contains an element of surprise (our expectations are not met or our assumptions are not valid) and the surprise forces us to consciously reflect about what are the possible causes behind our expectations not being met. Schön refers to this act of thinking as reflection-in-action. Reflection-in-action helps question the structure of assumptions behind knowing-in-action. In other words, we think critically about the thinking that led to a surprise opportunity or a challenge emerge, which, in turn, results in the restructuring of strategies or ways of framing or the understanding of the phenomenon itself. (Ibid. Pp. 26)

In Schön’s words, reflection gives rise to on-the-spot experiment, with the practitioner not being dependent on categories of established theory and technique but constructing a new theory of the unique case. At the same, he or she brings “repertoire of examples, images, understandings and actions” from the past experience to bear on a unique situation. (Pp 66)

In other words, the practitioner draws upon his or her mental model or frame of reference to understand and resolve the indeterminate situation and realise the stated purpose.

Schön argues that when someone reflects in action, he or she is a researcher in practice and builds a theory of the unique case.

While discussing the limitation of reflection-in-action, Schön mentions that artistry involves “intuitive knowing”, which a professional can describe as his or her own understanding. He mentions that it is possible that the description may not completely map the reality, but “incompleteness of description is no impediment to reflection…Although some descriptions are more appropriate to reflection-in-action than others, descriptions that are not very good may be good enough to enable an inquirer to criticise and restructure his intuitive understandings so as to produce new actions that improve the situation or trigger a reframing of the problem.”[25] (Pp. 277)

Schön recognises that there are situations where reflection-in-action may impede action. He mentions,

“There are indeed times when it is dangerous to stop and think. On the firing line, in the midst of traffic, even on the playing field, there is a need for immediate, on-line response, and the failure to deliver it can have serious consequences. But not all practice situations are of this sort. The action-present (the period of time in which we remain in the ‘same situation’) varies greatly from case to case, and in many cases there is time to think what we are doing.” (Ibid. Pp. 278)

However, he argues against seeing thought and action to be independent of each other by saying,

“If we separate thinking from doing, seeing thought only as a preparation for action and action only as an implementation of thought, then it is easy to believe that when we step into the separate domain of thought we will become lost in an infinite regress of thinking about thinking…Doing extends thinking in the tests, moves, and probes of experimental action, and reflection feeds on doing and its results…It is the surprising result of action that triggers reflection, and it is the production of a satisfactory move that brings reflection temporarily to a close.” (Ibid. Pp. 280)

In building the above argument, Schön introduces the idea of reflection-on-action, which involves stepping back and thinking about the “problematic situation”. However, he argues that not all situations exclude reflection-in-action and even the “fast-moving episodes are punctuated by intervals which provide opportunities for reflection.” (Ibid. Pp. 278)

I argue that reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action are equally important aspects of reflection practice. It is rare that we have complete information about any situation that we are dealing with, particular if we identify the situation to be an indeterminate situation. Whatever we do, we do it to influence something or someone at later point in time (sometime in future). Since the future is unknowable, we work with possibilities and probabilities using hypothesis generation and testing as a way of life. In other words, we work with possible and probable cause-effect relationships. We do that using formal methods sometimes, and sometimes just informally.

As a result of this experimental action-thinking-action loop, a practitioner learns and evolves his or her theory by reflection-on-action – thinking about something that has happened and what to do differently the next time. In other words, we bring past experience to bear on every subsequent situation – a repertoire of examples, images, understanding and actions – a mental model. In short, learning from experience and building a theory through reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action.

Role of Mental Models in Reflective Thinking and Reflective Practice

Both Dewey and Schön refer to the idea of mental model in their own way, Dewey using the idea of ‘capital stock of future experiences’ and Schön that of repertoire of examples, images, understanding and actions.

Philip Johnson-Laird mentions that we depend on mental models to anticipate the world and make decisions.[26] He credits Kenneth Craik to be on the first model theorists, quoting Craik’s book – The Nature of Explanation. Johnson-Laird highlights the following paragraph to make his point:

“If the organism carries a “small-scale model” of external reality and of its own possible actions within its head, it is able to try out various alternatives, conclude which is the best of them, react to future situations before they arise, utilise the knowledge of past events in dealing with the present and the future, and in every way to react in a much fuller, safer, and more competent manner to the emergencies which face it.”

We may note that the above paragraph informs about Craik’s thinking not very different from what we mentioned about Dewey’s thinking earlier.

Johnson-Laird also states that Edward C Tolman also developed a similar idea in the name of “cognitive map”. Johnson-Laird himself sees the mental models to be the representations in mind of real or imaginary situations and he states that we “construct mental models as result of perception, imagination and knowledge, and the comprehension of discourse.”

Natalie Jones et al. see mental models as “cognitive representations of external reality.” [27] They suggest that mental models represent incomplete reality, as people have limited ability to represent the world accurately. They also mention that the mental models are context-dependent and may therefore change with situation.

Donald Norman while discussing the idea of mental models makes the following observations:

“Mental Models are naturally evolving models. That is, through interaction with a target system, people formulate mental models of that system. These modes need not be technically accurate (and usually are not), but they must be functional. A person, through interaction with the system, will continue to modify the mental model in order to get a workable result. Mental models will be constrained by the user’s technical background, previous experiences with similar system, and the structure of the human information processing system.”

I argue that a mental model of the situation can never be complete, as we always work with incomplete information and the model is in any case a conceptual representation of a situation. Norman’s observation above requires us to consider the need for reviewing our own mental model over time, learn about other people’s mental models in similar situations and learn how the existing theoretical and empirical research in a given area can inform our mental model, allowing it to become more effective in helping us make choices and act to realise our purpose.

Norman also mentions that “people often feel uncertain of their own knowledge – even when it is in fact complete and correct – and their mental models include statements about the degree of certainty they feel for different aspects of their knowledge.” Given this observation, I, once more, see the need for sharing one’s mental model and learning from others.

Johnson-Laird suggests that mental models are the working models in an individual’s mind and have dynamic qualities. That is, a mental model not only involves representing the type of relationships in a situation but also the strength and the direction of these relationships and the way they are likely to change. While constructing a model, we make explicit as well as implicit inferences, some of which may be made without being consciously aware.

Given the evolving nature of a mental model, it is essential that we work together and help each other elicit their mental model and build a shared mental model, which will make it easier to work together, pool resources and realise a common purpose, all that with lower probability of conflicts and higher probability of success in organisational as well as personal context.

Carley and Palmquist[28] identify content analysis, procedural mapping and task analysis, and cognitive mapping as three approaches for representing mental models. They argue cognitive mapping to be the most appropriate approach to explore “the nature of shared knowledge in social groups….and “is often employed in expert-novice comparisons, studies of classroom learning and studies in decision making”.

If we can organise our experience and elicit the resulting mental model to share it with others, we can become far more effective as individuals and collectives (e.g., families, organisation, teams, etc.). While we do all of it implicitly or tacitly, it will definitely speed up learning and enhance our probability of success in indeterminate situations, if done explicitly. We can truly become a knowledge-society[29].

In this paper, I don’t intend to discuss how we elicit our own or other people’s mental model or build a shared mental model. I would, however, like to discuss a possible approach for development of reflective practice, using critical and reflective thinking skills.

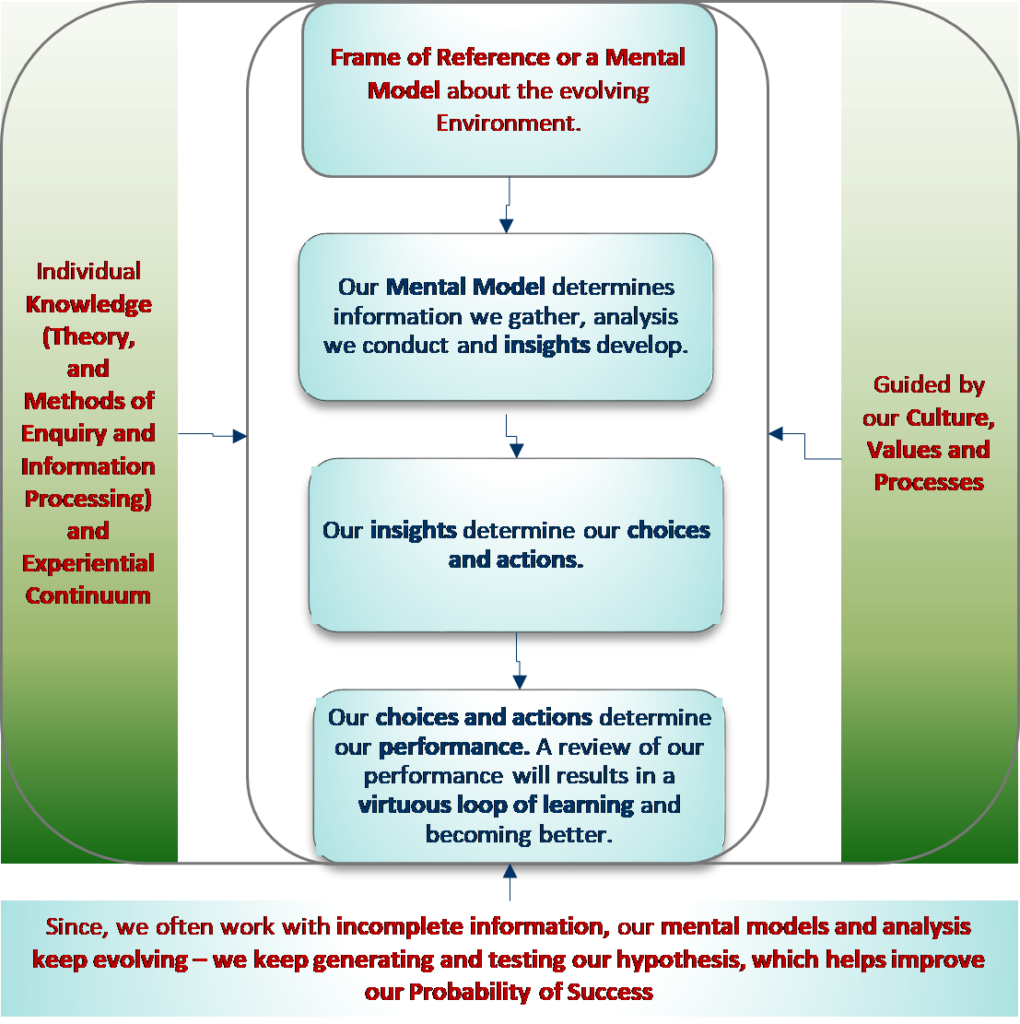

I propose the following to be a framework for reflective practice, which involves investment in building critical and reflective thinking capability, being aware of own and other people’s mental model and be willing to learn and evolve a shared mental model and thereby raising the probably of success:

Figure 2: Reflective Practice Framework

Building Reflective Thinking and Practice Capability

I argue that a person can think critically without being reflective, but a reflective thinker has necessarily to be a critical thinker. What distinguishes one from the other is that a reflective thinker draws upon his or her experience, a critical thinker does not have to do that. Consequently, the critical thinking framework is equally relevant for reflecting thinking. In addition, the reflective thinker uses his or her mental model as a source of knowledge, resulting in what Schön refers to as reflective practice.

In this section, I have made an effort to develop a framework that can guide us in understanding a ‘problematic situation or setting’ from critical and reflective thinking perspective. The framework draws upon the cognitive skills required for critical thinking, as presented in Figure 1. I then make an effort to ask a set of questions that help leverage our past experience and inform our understanding of the present situation.

While the questions below are based primarily on the ideas reviewed in the earlier sections, I have also drawn upon my experience in executive education and conversations with leadership and management teams during action-learning projects.

The purpose is to help an individual or a team to understand a phenomenon or a situation and/or make a decision (or decision recommendation) to solve a problem involving an opportunity to do better or meet a challenge.

I do recognise the fact that the understanding of a situation depends on the questions that we have asked, information that is available, assumptions that we have made and inferences and insights that we have drawn at any point in time. Our understanding will evolve with our knowledge, experience and the strength of critical and reflective thinking capability that we bring to the situation.

We have also attempted to distinguish how a reflective thinker can leverage his or her earlier experience to explore a given situation or a phenomenon.

Table 5: Reflective Practice, leveraging Critical and Reflective Thinking Capability

| Guideline Question | Illustrative Possibilities | Critical Thinker’s Questions | Reflective Thinker’s Questions | |||||||

| Interpretation (Categorisation, Decoding Significance and Clarifying Meaning) | ||||||||||

| Understanding the Problematic Situation or Setting | What is the nature of situation to be studied? | Simple determinate situation or a complex indeterminate situation. | What are some of the key dimensions that can help characterise the situation? | Have I experienced or studied a similar situation in the past? What can I bring forth from my earlier study or the experience? | ||||||

| Whose perspective am I studying the situation from? | Learner, Decision Maker, Analyst, Person Impacted, Advocate (as in Advocacy), etc. | What other perspectives can I bring to studying this situation? | What was my perspective at that point in time? Is it different now and why? What would I gain if I use the earlier perspective too? | |||||||

| What is my purpose in studying this situation? | Simply understanding a phenomenon, identifying an opportunity or making a choice or improving performance (solving a problem). | What possible purposes will study of this situation serve? | What was my purpose of study at that time? Is that relevant today too? How would it help if I combine the earlier purpose with the present one? | |||||||

| What are the decisions that are expected to be impacted by my findings? | Outline the possible impact of findings on the choices facing individuals involved. | Who is expected to make these decisions and what are likely to be their concerns? | Who was involved and what choices did he or she make and what was their criteria? | |||||||

| What are the criteria for decision to be made? | Guided by the purpose of study and the perspectives of people involved. | Is the set of criteria complete and internally consistent from everyone’s perspective? | How different is my choice of criteria now? How does it help me to combine the choices from the earlier situation? | |||||||

| Analysis (Examining Ideas, Detecting Arguments and Analysing Arguments) | ||||||||||

| Mental Models and Knowledge (Theory & Methods) | What is my frame of reference or point of view or the mental model? | An individual’s frame of reference is guided by his or her beliefs, values, knowledge and experience. | Is there another frame of reference that is different from mine, build around other perspectives? | How different was my earlier frame of reference? How would it help if I combine the two frames? | ||||||

| What are the key questions that will help me explore different aspects of this situation? | Different aspects that need to be analysed and/or evaluated will determine the questions. We will also be guided by our purpose, perspective and the frame of reference. | What different aspects must I explore to get a complete picture? | Was there a situation in my earlier experience where I discovered new aspects as I learnt about the situation? How can I modify my approach to exploration of the present situation? | |||||||

| What is my hypothesis for each aspect to be explored? | Hypothesis is guided by my perspective, purpose, frame of reference, etc. | What is theoretical framework that can guide my choice of questions and the related hypothesis? | Did my earlier exploration lead me to discover any framework or methods of analysis that I can apply now? | |||||||

| Evaluation (Assessing Claims and Assessing Arguments) | ||||||||||

| Information Processing | What information do I need to test each of my hypotheses and explore all aspects of this situation? | Information needs are guided by the hypotheses that to be tested and the relationships (among different variables) to be explored. | Is the available information clear, reliable, complete, precise, accurate, etc.? What kind of assumptions do I still need to make? | How did I deal with situations where I did not have the required information (use of proxies) or the available information was not clear, complete & reliable? | ||||||

| What is methodology (choice of methods and tools for information processing) for testing my hypothesis and finding answers to my questions? | Methodology is guided by standards of research in a given area and the situation to be studied. | Is the choice of methodology likely to provide me unbiased results that are representative and reliable? | What has been my experience with different methodologies (methods and tools) and how do I integrate my earlier experience with the choices I have to make in the present situation? | |||||||

| Inference (Querying Evidence, Conjecturing Alternatives, Drawing Conclusions) | ||||||||||

| Insights | What are my key findings and what is the story emerging from my findings? | Story is guided by the study purpose and is expected to cover all the relevant and significant aspects. Story is expected to reflect the evidence as well as insights. | Is my story internally consistent and true to the evidence provided by my study? | Have I come across a similar narrative earlier? How does that narrative relate to the present situation and the emerging story? | ||||||

| What are the implications of my findings and from the story built around these findings? | Implications are outlined from the perspective of person studying the situation or those impacted by the situation. | How do these findings impact me, and others involved? | How were others and I impacted while dealing with the earlier situation? | |||||||

| Explanation (Stating Results, Justifying Procedures and Presenting Arguments) | ||||||||||

| Choices & Actions | What is my decision recommendation? | Recommendation is to be based on decision criteria, given that it is complete and consistent from all the possible perspectives. | Are the recommendations consistent with the criteria? Are they largely feasible to implement? | How does my earlier experience help me choose my recommendations? | ||||||

I have also attempted to relate APA’s list of dispositions to guideline questions, which should enable an individual to assess if he or she is able to draw upon what the framework is expecting them to do (Table 6).

In summary I see a strong need to learn and practice using our critical and reflective thinking capability, given that we are likely to be dealing with indeterminate situations with incomplete information in a knowledge-society. While Dewey and Schön had laid down the foundation for reflective thinking and reflective practice, the critical thinking research shows us the way, by identifying the required cognitive skills and parameters for assessing the quality of thought, to transform some of their ideas into actions. I see the research field getting expanded in scope if we can explore further how individuals and teams have used and build their critical and reflective thinking capability while working with indeterminate situations and have raised their probability of success through reflective practice. I see the case-based research methods to be more effective in discovering how people learn and practice in their natural and social context.

Table 6: Reflective Practice and Relevant Disposition

| Reflective Practice Areas | Disposition to Draw From |

| 1. Understanding of Situation | • Inquisitiveness • Desire to become and remain well-informed |

| 2. Identification of Perspective | • Flexibility in considering alternatives and opinions |

| 3. Identification of Purpose | • Understanding of the opinions of other people |

| 4. Impact on Decisions | • Fair-mindedness in appraising reasoning |

| 5. Setting Up Decision Criteria | • Reasonableness in selecting and applying criteria |

| 6. Identification of Frame of Reference | • Open minded regarding divergent world-views • Alertness to opportunities to use critical thinking |

| 7. Identification of Areas for Exploration | • Clarity in stating the question or concern |

| 8. Setting up Hypothesis | • Prudence in suspending, making or altering judgments |

| 9. Identification of Methodology for Hypothesis Testing | • Trust in the process of reasoned enquiry |

| 10. Setting up Decision Criteria | • Reasonableness in selecting and applying criteria |

| 11. Building Story based on Findings | • Precision to the degree permitted by the subject and the circumstance |

| 12. Identification of Implications | • Self-confidence in one’s own abilities to reason |

| 13. Determining Recommendations | • Prudence in suspending, making or altering judgments |

[1] Critical Thinking: What it is and Why it counts by Peter A. Facione, 2015, accessed in April 2015 at http://www.insightassessment.com/Resources

[2] A Framework for Critical Thinking Research and Training by Susan C Fischer, in Training Critical Thinking Skills for Battle Command, ARI Workshop Proceedings, 2010, edited by Sharon L Riedel, Ray A. Morath and Timothy P. McGonigle.

[3] Critical Thinking: A Literature Review by Emily R. Lai, 2011, Pearson Research Report, accessed in March, 2015 at http://images.pearsonassessments.com/images/tmrs/CriticalThinkingReviewFINAL.pdf.

[4] Dewey and Schön: An Analysis of Reflective Thinking by Norman J Bauer, 1991, presented at the Annual Conference of the American Educational Studies Association, accessed through http://eric.ed.gov/ in April, 2015.

[5] Encyclopaedia Britannica, Philosophy of Education by Harvey Siegel, accessed on Oct 19, 2015

[6] Teaching Critical Thinking for Transfer Across Domains: Dispositions, Skills, Structure Training and Metacognitive Monitoring, Diane F Halpern, American Psychologist, April 1998

[7] Mr Henry Ford will find his view of the world to be at odd with today’s reality. Mr Ford is supposed to have asked, why it is every time I ask for a pair of hands, they come with a brain attached?

[8] A Framework for Critical Thinking Research and Training, Susan C Fischer, in Training Critical Thinking Skills for Battle Command: ARI Workshop Proceedings, Research Report 1777, US Army Research Institute for Behavioral and Social Sciences,

[9] Encyclopaedia Britannica, Philosophy of Education by Harvey Siegel, accessed on Oct 19, 2015

[10] Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction, Executive Summary, The Delphi Report, Peter A Facione

[11] Critical Thinking and Science Education, Science & Education, 11(4), Sharon Bailin, July 2002

[12] Universal Intellectual Standards, Linda Elder and Richard Paul

[13] Critical Thinking: Its Nature, Measurement, and Improvement, National Institute of Education, Sternberg, R.J., 1984

[14] Teaching Critical Thinking for Transfer Across Domains: Dispositions, Skills, Structure Training and Metacognitive Monitoring, Diane F Halpern, American Psychologist, April 1998

[15] Towards Critical Thinking as an Ethic, Alan Sears and Jim Parsons, Theory and Research in Social Education, Winter 1991

[16] Self-correct is included as a sub-skill under Self-Regulation by APA. Since we see self-regulation as an overarching skill, we prefer classifying it as a disposition on the lines stated by Halpern.

[17] The online Oxford Dictionaries describes disposition to be a person’s inherent qualities of mind and character, with temperament and nature listed as the synonyms. Similarly, Merriam-Webster’s Learners’ online dictionary describes disposition to be a tendency to act or think in a particular way or the usual attitude or mood or a person. Both accessed on May 5, 2016.

[18] In fact, I see my variance analysis presentation to be an unthinking application of my analytical skills.

[19] Critical Thinking: Its Nature, Measurement and Improvement, National Institute of Education, Robert J Sternberg, 1986

[20] Studies in Logical Theory by John Dewey, 1909, accessed in May 2016 through https://www.forgottenbooks.com/

[21] How We Think by John Dewey, 1910.

[22][22][22] Experience and Education by John Dewey, First Touchstone Edition, 1997.

[23] Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward A New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions by Donald A. Schön, 1987,

[24] Schön defines an indeterminate situation to be characterised by complexity, uncertainty, stability, uniqueness and value conflict. (Ibid. Pp. 6)

[25] The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action by Donald A. Schön, 1983.

[26] Philip Johnson-Laird, The History of Mental Models,

[27] Natalie A Jones, Helen Ross

[28] Kathleen Carley and Michael Palmquist, Extracting, Representing and Analysing Mental Models, 2011, Social Forces, 1992, 70(3).

[29] Cambridge Advanced Learners’ Dictionary and Thesaurus describes knowledge to be an understanding of information about a subject that you get by experience or study, either known by on person or by people generally. Oxford Dictionaries describes it to be as facts, information and skills acquired through experience or education – theoretical or practice understanding of a subject.