Proposed Reserve Bank of India Guidelines on Pay Regulation: A Perspective based on the European Experience

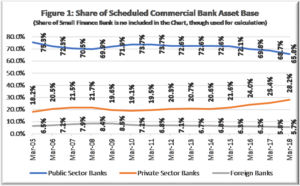

It is indeed timely for RBI to bring focus to pay regulation for private sector banks in India, as the private sector banks (including the foreign and small finance banks) have become significant players in the Indian banking sector. Together, they hold a share in 34.2% of assets as on March 31, 2018, up from 27.4% as on March 31, 2014 (Figure 1).

Source: STRBI_Table_No._01__Liabilities_and_Assets_of_Scheduled_Commercial_Banks, RBI Time Series Publications

We expect the share of private sector banks to go up further, as the public sector banks are struggling to manage the balance sheet challenges arising from large scale increases in non-performing assets during the recent years.

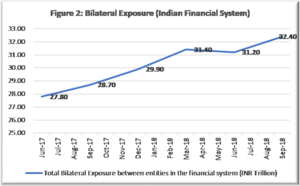

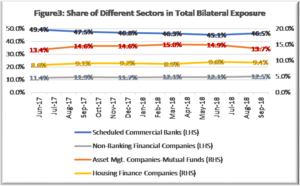

Another important aspect is that the interconnectedness in the financial sector has been on an increase, with non-banking firms and private sector banks holding large net payable positions to public sector banks, asset management firms and the insurance firms (Figures 2 to 4).

Source: RBI’s Financial Stability Report No. 18, December 2018, Pp 42.

Source: RBI’s Financial Stability Report No. 18, December 2018, Pp 42.

The recent episodes of corporate governance failures among bank as well as non-bank firms necessitate that the boards of directors and other stakeholders play an active role in managing risk (firm-specific risk and its impact on financial system risk) in the Indian financial sector.

Figure 4: Net Receivable and Payables Position

Source: RBI’s Financial Stability Report No. 18, December 2018, Pp 43.

These features of the Indian banking system are similar to those observed in the financial sector in developed economies. It is important, therefore, that the financial sector in India leverages the experience of developed economies, so that its growth builds on the right foundation and scales up well.

It is in this context, it is timely that the proposed guidelines by RBI on pay regulation of CEO, Whole Time Directors, Material Risk Takers and Control Function Staff, etc. seek to align the remuneration practices in the Indian private sector banks to the principles designed by Financial Stability Board (FSB).

In its introduction to the discussion paper, the RBI states the following:

“The compensation practices, especially of large financial institutions, were one of the important factors which contributed to the global financial crisis in 2008. Employees were too often rewarded for increasing the short-term profit without adequate recognition of the risks and long-term consequences that their activities posed to the organizations. These perverse incentives amplified the excessive risk taking that severely threatened the global financial system.”

Post the global financial crisis (GFC), some of the pay practices that were perceived to encourage imprudent risk taking (e.g., inadequate governance, risk misalignment of incentives, golden parachutes including generous pension entitlements, quantum of bonuses, insufficient disclosures, and proliferation of unhealthy pay practices, such as multi-year guarantee bonuses and retention packages and complex pay arrangements) attracted regulators’ attention. General media contributed to compensation becoming an issue of public interest and debate, as banks had to be bailed out using tax-payers’ money.

Given that the financial industry is globally inter-connected, and the magnitude of crisis was severe, any effort at improving its stability required global coordination, and that’s where the FSB provided its leadership. FSB Principles for Sound Compensation Practices are expected “to reduce incentives towards excessive risk-taking that may arise from the structure of compensation schemes. They are not intended to prescribe particular designs or level of individual compensation.”

FSB, while laying out the principles mentions that “most governing bodies of financial firms (henceforth board of directors) of financial firms have viewed compensation systems as being largely unrelated to risk management and risk governance. While voluntary action is desirable, it is unlikely to effectively and durably deliver change given competitive pressures and first-mover disadvantage. The global supervisory and regulatory infrastructure is an appropriate vehicle for making sound compensation practices widespread.”

Given that the RBI guidelines draw upon the FSB Principles, it is useful to reflect on 10-years of experience on pay regulations in the UK and Europe, which were also based on FSB principles, to find out if there are lessons that could be relevant in the Indian context.

1. Evolution of Pay Regulation in the European Financial Sector

The developed economy financial sector is complex, relatively less regulated (compared to Indian financial sector) and inter-connected. The complexity emanates from multiplicity of legal entity structures, variety in business models, varying scale of operations across entities, and the range of businesses that different firms pursue. The main contributors to entity-specific or systemic risks are seen as bank activities in the capital markets, mainly the investment banking, trading operations and alternate investments businesses. Retail and wealth management present risks, which are different in nature, and generally deal with conduct issues, such as mis-selling of products and sales incentives plans, which encourage aggressive selling. Given the inter-connectedness of the sector, and indeed the economy, however, risks do not remain isolated to any particular business areas or firms.

Compensation guidelines have focussed on the need to have adequate senior level (Board or its Remuneration Committee or RemCo) oversight over pay decisions and requiring financial firms to have a comprehensive remuneration policy to cover various aspects of pay such as risk-alignment, governance, pension policy and pay structures. Firms were also expected to ensure that their remuneration policies, practices and procedures are clear and documented.

Regulators in Europe were also concerned about excessive pay in the industry and introduced 2:1 bonus-cap to moderate it. Bonus-Cap has greater applicability in investment banking and capital markets, where variable pay (bonus) is generally in multiples of the fixed pay. It is noteworthy that UK government did not agree with the 2:1 bonus cap requirement and even challenged it in the EU Court.

Pay regulation in UK, and to a great extent in EU, has emerged as the most comprehensive and far reaching in scope. In the UK, it started with Remuneration Code, and in later years, extended into other broader areas, such as senior management regime, ring-fencing/structural reform, and recently beginning to pay emphasis on changing the culture for good, all of which have indirect pay implications.

With the passage of time, regulators expected and encouraged firms to go beyond meeting the minimum regulatory requirements and adopt the best practices. There are expectations, for example, to increase the number of Material Risk Takers (MRTs) beyond the baseline requirements outlined in Regulatory Technical Standard (RTS) 1 or to set up RemCo in legal entities, where risk impact and/or the nature of business warrants it.

2. Purpose of Proposed RBI Guidelines (As extracted from the Guidelines Document)

The proposed guidelines contain new pay provisions, which aim to ensure:

- Effective governance of compensation, with the Board being responsible for design and operation of the compensation system, reviewing that the compensation system works as intended and ensuring the independence of risk and financial staff.

- Effective alignment of compensation with prudent risk taking, i.e., compensation is adjusted to various risks, is symmetric with risk, payment schedules are consistent with risk horizons and the compensation mix (cash, equity or any other form) is consistent with risk alignment.

- Effective supervisory oversight and engagement by stakeholders, i.e., the supervisory review is rigorous and sustained and the firm discloses timely, adequate information to ensure that the stakeholder engagement is constructive.

Given that the objectives outlined above are on the same lines that articulated by FSB, we have focused on reviewing the UK and the European experience to see if the FSB guidelines have achieved or made material progress towards achieving the above-mentioned objectives. We have also highlighted the areas where India can learn from the UK experience.

2.1. Effective governance of compensation

Big banks have established the required, some would say complex, processes for assessing their pay decisions from a variety of perspectives. There is also an increased awareness, and less appetite, to approve or encourage pay practices that could potentially act against firm’s interest. In addition, there is also a close relationship between significant banks and regulators. Finally, there are now processes to assess how well firms are doing in terms of pay governance, and also, in the unlikely event of a process break down, to create timely awareness and means to identify and correct them.

Remuneration committees (or their equivalent bodies) with responsibilities for the design, approval and oversight of remuneration policy provide a structured accountability framework, if systemic or significant pay issues come to light.

2.1.1. What has enabled the progress in the right direction?

The above progress has happened over the years with a significant investment of time and efforts from the regulators, senior management, and Human Resources functions. Control functions, such as risk, compliance and internal audits, too had their learning curve and investments of effort, as they had to understand how to provide best support on pay decisions, besides covering their own broader and expanding remits.

The processes, even after they are embedded in the organizations, require significant information and overheads for sustaining them. In the case of complex (multi-legal entity; multi-business; multi-jurisdictional) firms, regulations have also led to complex governance frameworks, which could itself be seen as an operational risk.

The amount of progress, however, can be broadly attributed to three main factors:

- Firstly, regulators were aware that the task of pay regulation, in a complex and dynamic industry, requires time, effort and continuous engagement with stakeholders. There was also an understanding that it will take firms time and effort to establish the required processes and the regulation will create administrative burden for the sector;

- Secondly, regulators adopted the concept of proportionality, which meant that not all banks are same in terms of their risk impact to the economy. Attention was therefore focussed on the significant banks (Tier I banks), which were big in size, internal complexity and risk profile. Tier I and 2 firms were expected to comply with pay regulation to a greater extent, while Tier 3 firms had a choice with respect to some of the pay provisions. This provided some capacity to regulators to focus on where risks mattered the most. It also allowed the administrative burden on the smaller firms to be low;

- Thirdly, the pay regulation became increasingly specific about various aspects that it covered with the passage of time. A good example is provided by the pay structure for the MRTs. It started with the mandatory requirements for minimum deferrals, and have over the years included aspects as what qualifies as share linked instruments (as 50% of variable needs to be in share-linked deferrals), need for retention period post vesting, and lack of dividends, while the deferred shares are unvested.

2.1.2. What can India learn from the UK and European Experience to ensure that the Indian Bank Boards are able to ensure effective governance of compensation?

Perhaps an important lesson for bank boards is to encourage organizational wide-conversations, starting within their own members and Executive teams, as to what is the right thing for the firm to do, what are the broad processes and resources needed, and to ensure that the pressures of meeting the deadlines do not obfuscate the real issue and problem that the pay regulation is trying to address. An important point for the Boards to bear in mind is that pay regulation is not an end in itself. It has a purpose behind it, and it is important that conversations and resources are mostly around the purpose.

Another key lesson is that the culture matters as well when it comes to effective risk management. UK regulators have started encouraging firms to pay attention to culture2, as pay regulation can achieve only so much on its own. Culture building takes time and could perhaps happen only with Board’s active support.

Finally, Boards should consider in their approach the evolving nature of regulations and that they move from being general to becoming more specific. This will allow business leaders to not consider pay compliance as a “project” in itself, but as means to an end (e.g., more robust bank). In the UK/EU contexts, in the beginning, the regulatory guidance was largely principle based and general in nature. Different firms applied it differently leading to an uneven playing field and practices. This is important area, because an uneven playing field allows both the firms and employees to benefit from regulatory arbitrage in ways that negate the spirit of pay regulation.

2.2. Effective alignment of compensation with prudent risk taking

Since risk-alignment of compensation was one of the main drivers behind the pay regulations, it has seen continuous efforts and progression over the years. It has evolved on the following lines:

- Identification of employees, whose activities have a material impact on risk profile;

- Structuring their pay differently (mandatory minimum deferrals; minimum 50% in share-linked instruments, etc) to ex-post risk adjustment (malus and clawback);

- Determining bonus pools based on ex-ante risk considerations to encouraging firms to have a culture, which does not encourage risk-taking;

- A closely related area was also the excessive pay. It was reasoned that the objective of risk-taking is to earn higher bonus, and therefore, if the pay itself is capped, so the thinking went, the risk-taking would also get capped. A bonus cap of 2:1 (variable to fixed pay) was introduced in EU in the year 2014 to in-scope firms.

As with remuneration policy and governance frameworks, firms went through a learning curve in the above four areas, all the while focussing on the risk-alignment effects of pay.

2.2.1. Identification of Material Risk Takers (MRT)

The guidelines for identification of Material Risk Takers (MRT) evolved from being very general in 2009/10 to being more specific when the Regulatory Technical Standard (RTS) was published in 2014. While there are still areas where discretion could play a role, RTS has in many ways levelled the playing field by providing a set of consistent principles, the lack of which previously led to banks, even comparable banks, having varying number of MRTs. This not only had implications for morale, as MRTs are very sensitive to onerous pay regulations, but also for retention and hiring. In many respects, uneven playing field defeats the purpose of pay regulation, as employees could leave and go to a competitor, where s/he will not be MRT. There was also a recognition in UK and EU that all MRTs are not equal in terms of their risk impact, which led to creation of additional categories of MRTs with different minimum deferral schedules.

The proposed RBI guidelines seem to be very general, and it is likely that they will create an uneven playing field.

2.2.2. Pay structures to reflect risk profile

While the regulations expected firms to design pay-structures in a way that reflected the nature and time-horizon of risks with minimum mandated requirements for the MRTs, achievement of be-spoke risk aligned structures proved difficult in practice. Apart from the fact that it is difficult to design an all-encompassing risk-based pay structure, there was also the issue of uneven playing field, which essentially encouraged firms to apply the minimum standards expected, as anything more onerous than the minimum required would make talent retention, hiring and even employee morale management a difficult challenge. This was perhaps aptly labelled as “first mover disadvantage”.

It is worth noting that the pay structures became progressively very onerous (for the MRTs) and for the firms (from the administrative and system’s point of view). As mentioned above (2.2.1), there are now different categories of MRT with different deferral schedules, and the deferred shares being subject to additional retention periods and do not receive dividends during the vesting period.

The present RBI guidelines suggest that a minimum deferral of 60% and length of retention period to be determined by firms. If the idea is to have a small number of MRTs – and the experience is that there no one “right” number for the number of MRTs for a firm – then minimum 60% deferral perhaps seems right, as only the senior most members will be identified as the MRTs.

A crucial question is:

Is it possible for senior managers to know and be aware of all the risks, particularly in the capital market context?

If not, then it would mean that some mid-level employees also need to be classified as MRT. While organizational design certainly plays an important role in determining who should be classified as MRT, this also has an industry and sector specific angle that perhaps is best addressed at the level of regulators. Regulators in UK have encouraged firms to go beyond the senior most levels, and also identify staff at mid-senior levels as MRTs. The mandated minimum deferrals for some of these MRTs is 40%, as the risk impact arising from their roles is not seen to mandate a minimum of 60% deferrals.

RBI guidelines also stipulate that minimum of 50% of pay would be in bonus. This de-facto makes 50% a guaranteed variable pay, and therefore almost a fixed salary. While UK and EU regulations emphasise the need to have skin in the game through variable pay, there is no “minimum” variable pay requirement. Variable pay could also be zero in case individual or business performance requires no bonus pay out.

2.2.3. The 2:1 bonus-cap

The 2:1 bonus-cap (i.e., variable pay is capped to 200% of fixed pay; shareholder approval needed for the cap to be 200%) is one of the most debated aspects of the pay regulation in UK and EU. Incidentally, the UK government was not in favour of this cap, and even launched a legal challenge to it in the EU courts.

Interestingly, the introduction of bonus-cap has had an unintended consequence of increase in the fixed pay of MRTs through introduction of new allowances, which were paid in the early days of cap using different pay practices3. These allowances were based on concept of re-balancing of pay, i.e., shifting part of the expected variable pay into the newly formed allowance. From the practicing manager’s point of view, they created an inflexible compensation cost, and reduced the flexibility available previously, when depending on performance at the firm, business and individual level, bonus amounts can be flexed down to a much greater degree.

2.2.4. Application of Risk-Adjustments

While the processes for the ex-post risk adjustment were conceptually easy, in practice they required a policy and governance framework to ensure that reasons for ex-post risk adjustment (malus/clawback) are established in a fair, transparent and correct way. This also needed a close relationship between HR and the Control functions (namely, Compliance, Risk and Internal Audit).

Given that RBI guidelines leave it to banks to decide, except in case of NPA, on the malus and clawback modalities, it is unlikely that a level playing field or consistent practices will emerge. There is also a need to clarify a minimum time window within which clawback is applicable. In the UK context, it is 7 years from the date of award of bonus. Perhaps, a more difficult aspect is the determination of ex-ante risk adjustments to the bonus pool. From the anecdotal accounts, it seems like a work in progress, and each firm needed to evolve its own methodologies to get the “in the range” answer. The proposed RBI guidelines recognise this, but as the implementation goes into effect, there will be a need to develop and share best practices in the area.

2.2.5. What can India learn from the UK and European Experience to ensure that the Indian Banks can achieve effective alignment of compensation with prudent risk taking?

The alignment of compensation with risk-taking is more effective, when it is done at various stages of the compensation process. While each of these stages rely on different matrices, time-horizon, quality and certainty of information, and processes involved, it is perhaps useful to have a big picture, so that these stages are inter-connected and back-tested.

Perhaps a relatively easy stage deals with the ex-post risk-adjustment, where misconduct or any other negative risk events have crystallised, which could be traced to individual or group of individuals. This would involve risk-assessment before each deferred tranche/slice gets vested.

Ex-ante adjustment is conceptually more challenging, as it requires developing firm-specific methodologies on how risks could play out in future and requires adjustments to the bonus pools. This process is helped if the firm has at the strategy level insights on the main banking activities at the operational perspective and what risks matter or could matter. This requires a close stakeholder management at the strategic and operational level between Reward (and HR) as well as Control functions (namely, Risk, Compliance and Internal Audit).

It is also important to develop firm-wide policies and processes, including changes in the incentive plans and employee contracts, to ensure that employees (mostly MRTs) are not only aware of the risk-impact of their actions on their pay, but also there are fair and transparent processes that exist to address the ex-post adjustment, particularly at individual or group levels, when the need arises.

Finally, banks also need to have processes and practices that allow information to become available in a timely manner for any reasonable and good quality risk-assessment for ex-ante or ex-post performance to happen, preferably as soon as risk-event crystallises. This requires building an across the board organizational capabilities in various areas, including in risk and compliance functions, and developing a framework on how various kinds of risks bear upon pay outcomes.

2.3. Effective supervisory oversight and engagement by stakeholders

The requirement to disclose information in a way, which is accessible and easy to understand was part of regulatory requirement, post the GFC. Over the years, the requirements have been finessed further, and as a result, there is a good information available to various stakeholders including investors. The information is also sent to regulators by the in-scope firms and the findings are used and published by the European Banking Authority (EBA)4. It is not clear from the guidelines, if RBI plans to do the same. While higher transparency and disclosure has value in and of itself, its potential probably could be maximised if regular analysis is published on the pay trends.

Current RBI guidelines do not specify how the regulator (RBI) plans to provide supervisory over-sight to the pay regulation, except for WTDs/CEOs of private and foreign banks. Does it plan to ask for and get involved in decision making for other MRTs as well, and if yes to what extent?

In the UK context, there are structured time-lines when certain processes and/or submissions are to be completed, and over the years processes have crystallised in a way that makes it easier for banks to plan. For example, Banks need to keep information prescribed in the Remuneration Policy Statement (RPS) 5 templates. In addition, there are tables5 (databases on MRTs, MRT exclusions, and Malus), which make it easier for banks and regulators to engage in effective implementation. Perhaps, one reason why the pay regulation has got institutionalised to the extent it has is because of the recognition that it is a new territory for all, and it is important to keep building on experiences.

2.4. What can India learn from the UK and European Experience to ensure that it is able to achieve effective supervisory oversight and engagement by stakeholders?

Both regulators and individual firms have made significant investments in resources, efforts and relationships to ensure that progress happens in the areas of pay regulation, and it perhaps is still a work in progress. Few key areas to consider, as the implementation is initiated, are as follows:

- It is perhaps important to be realistic and accept that there will be unintended consequences and learnings along the way for all stakeholders. It is therefore very crucial that a trust based relationship is established, which recognises that pay regulation is a new territory for everyone;

- In the UK/EU contexts, the regulators have identified processes (including information requirements and templates) and requirements that firms are to follow. This covered not only mandating the responsibilities to RemCo, but also broader areas, such as engagement with shareholders (including information to be provided) on pay matters and seeking regulatory approvals and guidance on various important pay matters. Such processes and requirements have not only established accountability and audit trails, but also a desire to make improvements in pay practices. Proposed RBI guidelines, at this stage, do not seem to include any ongoing or hands-on supervision, except for CEO/WTD and foreign banks;

- In the UK/EU contexts, financial firms were divided into various proportionality tiers, and regulation was applied on the basis of these tiers. This allowed regulators to focus their resources and focus on Tier I and II banks, where risk impacts to the firm and broader economy were more. It is an important concept, and it will be useful to apply this in the context of Indian banking sector as well, as banks differ in terms of their scale, scope and risk impact;

- As outlined in the previous sections, it is important to have a certain base-line requirements on various provisions (deferrals requirements, identification of MRTs, malus and clawback clauses, and oversight and non-compliance aspects) being laid out from the regulators, as opposed to replying on the judgement of individual banks. This will ensure some consistency and ensure that banks, which are applying it in the right way, are not at a disadvantage;

- The concept of mandatory deferrals, as UK experience has shown, needs to be further strengthened by the application of buy-out rules, so that MRTs could not change jobs and erase the implications of their past performance on their deferrals by having the bonus bought over by the new employer.

3. General lessons

Given a history of the last 10 years, it is useful to assess how well the pay regulation has delivered so far? It is tempting to assume that an experience of 10 years would give definite answers. However, this is a complex discussion with varying views, and while answers are not easy to find, it is possible to get few insights from the experience so far.

3.1. Lessons at the Level of Economic System

The proponents of pay regulation see it as a success (barring few exceptions) given that banking scandals have come down, and high pay packages do not make headlines as often. It is, however, useful to remember that the pay regulation is implemented in economically mute contexts. In terms of anecdotal observations, risk taking in banking goes up when the “animal spirits” of the boom times take over. Given the economically tough environments and higher capital needed, banks have been forced to cut down costs (including pay packages) to meet their return-on-equity objectives. Tough economic conditions just enabled banks to be able to do it easily, as bankers did not have lots of places to go to. Pay regulation happens to be there, but it is important to make a distinction between causality and correlation.

Few additional lessons are as follows:

- Given the general regulation, increasingly higher number of financial activities are moving into Alternate Investment or other less regulated sectors, where the risks for the financial system are now getting concentrated. This could imply that pay regulation is perhaps addressing an issue that is not in sync with the risk transitions that are happening at the macroeconomic level;

- It is also likely that pay regulation and other regulations have started encouraging talented employees to go to higher paid jobs in less regulated sectors, such as hedge funds and private equity. In this context, perhaps excess regulation has made banking a less attractive place for the talented employees needed for the well-functioning of the sector;

- The experience form UK/EU suggests that pay regulation does require significant resources in terms of time, efforts, team building, system and infrastructure, and costs. Though UK/EU legislation has been comprehensive, and therefore resource requirements more acutely felt, it is perhaps fair to generalise that firms with less onerous pay regulation to comply with will also likely end up underestimating the magnitude and scope of the resource commitments needed. Additionally, these resource implications are not limited to Reward (Human Resources), but span across Control functions (such as Risk, Compliance and Internal Audits) and business leadership levels. One possible way to help banks to deal with the implementation challenge isis to give them enough of lead times, and, to the extent it is practical, build consensus and avoid any surprises in terms of new provisions or requirements;

- The EU experience to reduce pay has led to increase in fixed pay to be able to comply with bonus cap and pay the same level of pay as before. This increase in fixed pay, as noted earlier, made the compensation cost base more inflexible.

3.2. Lessons at the Level of Individual Banks

From the implementation perspective of a bank, the initial phase of the work almost always involves the task of meeting the deadlines. There are limited resources (including time) to answer the question, as to what is the right thing for the firm? What are the key risks that firms should address, who and how many MRTs should the bank have, do the performance management systems allow performance to be risk-assessed at various levels including at the level of individuals? What bonus methodologies and ex-ante risk process best suits business risk and model of the firm?

Even without the above questions, the challenge of meeting the deadlines technically requires a good amount of strategic and administrative effort, something which both regulators and firms end up underestimating. This is not limited to Human Resources or Reward function, but also involves Control functions, such as Risk, Internal Audit, and Compliance. A recent article6 by one of the co-authors (Dr Anujayesh Krishna) conceptualised the different stages and challenges that individual firms go through while implementing these changes.

Another important lesson at the level of banks is to ensure that business and HR leadership is engaged in the communication process with the employees. Although regulations in UK/EU expect firms to make the employees aware, it is important that all employees (and not just MRTs) know about the pay policies and the impact of risk and conduct issues on their pay. A continued awareness on how the pay decisions in future will be guided by risk and similar business focussed considerations is an important aspect of overall culture building.

While, the proposed RBI guidelines are not as comprehensive as current EU guidelines, and that is perhaps a good news, experience on pay regulation suggests that it does lead to large amount of overhead, band-width requirements and resources before it bears the fruits for the firm and system as a whole.

4. Experience with Pay Regulation Elsewhere

Historically, regulation that attempted to reform pay had unintended consequences. In the US, the mandatory disclosure of Executive compensation in 1993 is alleged to have led to an increase in CEO compensation as CEOs could use the public information to benchmark themselves and demand higher pay7. Similarly, in the US, while the aim of tax deductibility limitation of IRC Section 162(m) was to reduce excessive pay, it ironically led to an increase in pay8.

5. Summary

An important point while finalising the guidelines is to remember the problem that the guidelines are expected to solve, and then customise the guidelines accordingly. Consistency with FSB and risk-alignment of pay with performance is indeed required. However, it is important to be aware of unintended consequences that de-contextualised guidelines and unevenness in the playing field could lead to. It is also important to remember that pay regulation takes time, and various processes, including bonus pool methodologies, ex-ante and ex-post risk adjustments, and developing operational framework require significant on-going effort before they show results. Pay regulation is welcome, particularly when the health of economy depends on it. At the same time, it is important not to depend on it to solve complex risk and governance problems. At its best, effective pay regulation will not make them any worse. Appendix A contains specific feedback on the proposed RBI guidelines.

Appendix A: Specific Feedback on Proposed RBI Guidelines on Pay Regulation in Private Banks

| Page: RBI Guidelines | Guideline | UK/EU Experience6 | Comments |

| Page 5 | 1.1 Guideline 1: Compensation Policy | This has led to industry taking a holistic look at compensation aspects of the firm. | In the UK context, regulators have also identified specific areas and provided templates5, which contain various information heads under which firms should consider and implement remuneration policy. There are also requirements for audits and regulatory oversight into the implementation of policy at the function (reward) level. |

| Page 6 | 1.2 Guideline 2: Nomination and Remuneration Committee (NRC) | In the UK context, it also involves, inter-alia, that these Committee should have access to independent opinions/consultants, and resources. | In the UK context, this requirement is at Tier I and Tier II legal entity level, though firms are being encouraged to set them up where risk impacts could be significant.

|

| Page 7-8 | 2.1.1 Fixed pay (FP) and Perquisites

And

2.1.2 Variable pay (VP) | In UK and EU, firms increased fixed pay through introduction of new allowance3. | To the extent, UK & EU experience is generalizable, implementation of 2:1 bonus cap is likely to lead to high fixed pay (perhaps through introduction of fixed allowance) and an inflexible fixed cost base for the bank. There are administrative issues as well, such as maximum variable to mid-year joiners, or part-year MRTs/Directors. Finally, banks may simply pay more in perquisites (assuming they are not encash-able). |

| Page 8 | 2.1.2 (b) Limit on Variable Pay:

“… but shall not be less than 50% 9 of the Fixed Pay”. | There is no such minimum for variable pay in UK, which could be zero, if needed. | This wording in RBI Guidelines de-facto implies a guaranteed bonus regardless of performance and affordability. It is unlikely to be the intention, and perhaps it can be made clearer |

| Page 8 | 2.1.2 (c) Deferral of Variable Pay “For such executives of the bank, in adherence to FSB Implementation Standards, a minimum of 60% of the total Variable Pay must invariably be under deferral arrangements.” | In UK/EU, minimum deferral to MRT population is 40% and 60%, though banks can do more than 60% deferrals. | In general, all MRTs do not have equal risk impact, and there are tiers, as the PRA regulation in UK shows. Thus, a minimum deferral of 60% to all MRTs seems harsh, particularly if the intention is to include broader population as MRTs.

There are certain rules (such as de-minimis, or less than 3 months in MRT role), where certain rules do not apply (in UK), though this may change with CRD V. Additionally, certain rules do not apply for firms, which are in Proportionality Tier III |

| Page: RBI Guidelines | Guideline | UK/EU Experience6 | Comments |

| Page 10 | 2.1.3 Malus/Clawback | While banks were encouraged to identify set of criteria and formal policy on malus and clawbacks, there are base-line requirements, such as 7 years for clawbacks period, as well as identification of conditions when malus and clawback could apply. | Currently, it is left to the Banks to formulate their own policies, which could lead to an uneven playing field. |

| Page 10 | 2.1.4 Guaranteed Bonus

| It is not very clear from the guidelines, if 2:1 bonus cap will apply to Guaranteed Bonus, and if yes, how. | |

| Page 12 | Guideline 6: Identification of Material Risk Takers of the bank | The guidelines evolved over last 10 years, and became more specific and comprehensive, particularly after the publication of Regulatory Technical Standards (RTS) in EU in March 2014.1 | Current guidelines are general, and in many ways, reflect the situation in UK/EU in 2010. In UK/EU context, this led to inconsistencies in how banks have applied and therefore number of MRTs they had. This improved after the publication of RTS in March 2014. |

| Page 12 | 2.4.2 “Banks are advised to refer to the BCBS report entitled Range of Methodologies for Risk and Performance Alignment of Remuneration…” | This takes time for banks to understand and come-up with something that works for them and meets the regulatory objectives.

This also requires Control Functions (such as Risk, Compliance and Internal Audit) to take a leap forward in their own internal processes to be able to support the regulatory goals. |

Most of the risks in the context of financial firms in developed economies had a strong capital market risk angle. This will perhaps require some de-contextualisation in Indian context, to recognise that while there are similarities, there are also differences in how the financial systems work. |

| Page 13 | Guideline 7: Disclosure | In UK/EU, disclosures are also accessed, among other stakeholders, by regulators, who analyse trends and movements. | It will be useful, if there is a process to review, analyse and publish the results of disclosures. In EU, EBA publishes4 the benchmarking reports, and this possibly also informs on policy choices later. |

References

- Regulations. Commission delegated Regulation (EU) No 604/2014 of 4 March 2014. Official Journal of the European Union. 6.6.2014. < https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014R0604&from=EN>

- Please see FCA (one of the UK regulators) paper on Culture Transformation: https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/discussion/dp18-02.pdf

- EBA Report on Remuneration and Allowances. EBA Report. On the application of Directive 2013/36/EU (Capital Requirements Directive) regarding the principles on remuneration policies of credit institutions and investment firms and the use of allowances. 15 October 2014. https://eba.europa.eu/documents/10180/534414/EBA+Report+on+the+principles+on+remuneration+policies+and+the+use+of+allowances.pdf

Opinion of the European Banking Authority on the application of Directive 2013/36/EU (Capital Requirements Directive) regarding the principles on remuneration policies of credit institutions and investment firms and the use of allowances. EBA/Op/2014/10. European Banking Authority. 15 October 2014. < https://eba.europa.eu/documents/10180/657547/EBA-Op-2014-10+Opinion+on+remuneration+and+allowances.pdf>

- The EBA Benchmarking report 2018 is available at the link below:< https://eba.europa.eu/-/the-eba-observes-a-decrease-in-high-earners-in-2016-and-differences-in-remuneration-practices-across-the-eu>

- For reference: Remuneration Policy Statement template for Level 1 firms can be accessed at: <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/prudential-regulation/strengthening-accountability/rps-template-level-1-firms.doc?la=en&hash=C24B80DBA9490E8D38933B44C84392B1CC2170A9&hash=C24B80DBA9490E8D38933B44C84392B1CC2170A9>

Links to few other tables and templates are provided at: < https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/key-initiatives/strengthening-accountability>

- A typical change management trajectory followed by financial firms in UK while implementing pay regulation is discussed in the paper below:

Implementing Reward Regulations in Financial Industry @ https://www.ideassansideology.org/implementing-reward-regulations-in-financial-industry-a-stage-model-of-change-management/

- Ariely, Dan (2008), Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces that Shape Our Decisions. London: HarperCollins E-books. Dan Ariely described this in the following way: Location 375 of 4317 on Kindle

“An ironic aspect of this story is that in 1993, federal securities regulators forced companies, for the first time, to reveal details about the pay and perks of their top executives. The idea was that once pay was in the open, boards would be reluctant to give executives outrageous salaries and benefits. This, it was hoped, would stop the rise in executive compensation, which neither regulation, legislation, nor shareholder pressure had been able to stop. And indeed, it needed to stop. In 1976 the average CEO was paid 36 times as much as the average worker. By 1993, the average CEO was paid 131 times as much. But guess what happened. Once salaries became public information, the media regularly ran special stories ranking CEOs by pay. Rather than suppressing the executive perks, the publicity had CEOs in America comparing their pay with that of everyone else. In response, executives’ salaries skyrocketed. The trend was further “helped” by compensation consulting firms (scathingly dubbed “Ratchet, Ratchet, and Bingo” by the investor Warren Buffett) that advised their CEO clients to demand outrageous raises. The result? Now the average CEO makes about 369 times as much as the average worker—about three times the salary before executive compensation went public.”

- Murphy, Kevin J. and Jensen, Michael C. (2018). The Politics of Pay: The Unintended Consequences of Regulating Executive Compensation. Center for Law and Social Science. Research Paper Series No. CLASS18-8. Legal Studies Research Papers Series No.18-8. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3153147