Enhancing India’s ‘Ability to Grow’: Making a case for Increased Organised Sector Employment, particularly the Government Sector

India is a low per-capita economy with 1.3 billion people. Given that the population growth is expected to slow down further, it is the per capita income that would drive India’s growth. In the long run, it is the household earnings that drive private and government consumption growth, which, in turn drives, the demand for investment or gross capital formation. However, if the level and/or the quality of household earnings is low, the opportunity to improve the quality of life is lost very quickly – phenomenon that is also referred to as the middle-income trap.[1]

A family can raise the level of its earnings and thereby the quality of its life only in following ways:

- Build a business that provides stable profits in excess of cost of risk capital, which requires that the family has the required risk capital and is willing to risk.

- Find low-risk employment that provides stable earnings and hence helps build the ability and willingness to spend and invest.

- Seek financial support from others, i.e., government and charitable organisations – domestic and international.

If a family does have stable earnings through business and employment, it can raise debt to grow its business and/or increase its consumption. Credit can, indeed, support growth in consumption and investment but it cannot be the main driver of growth beyond a point. Similarly, there is an obvious upper limit on the availability of resources for financial support from charitable organisations.

Virtuous Relationship between Family Earnings and Economic Growth

Organised sector, public as well as private, is expected to assist families in earning stable incomes – through employment that pays a wage linked to cost of living and sub-contracting work (to smaller businesses) where the organised firms, particularly the larger ones, bear the risk that the smaller firms are not in a position to bear.

A large, organised business is expected to be good at managing risk, as it enjoys economies of scale and can hire people who have knowledge and experience to assess and manage risk. A small business does not have these advantages. Over time, we do expect the smaller businesses too to improve their ability to take and manage risk.

The government is expected to lead this effort through investment in economic as well as governance services by creating jobs that provide basic (e.g., sanitation, water, education, healthcare, etc.) and governance (e.g., regulation, security, administration, etc.) services. Given its sovereign nature, the government can take risks that even the large private sector firms would find difficult to manage.

In short, the government and the organised private sector employment is the main source of stable earnings across the economy.

India’s Consumption and Investment Growth has been trending downwards even before the pandemic

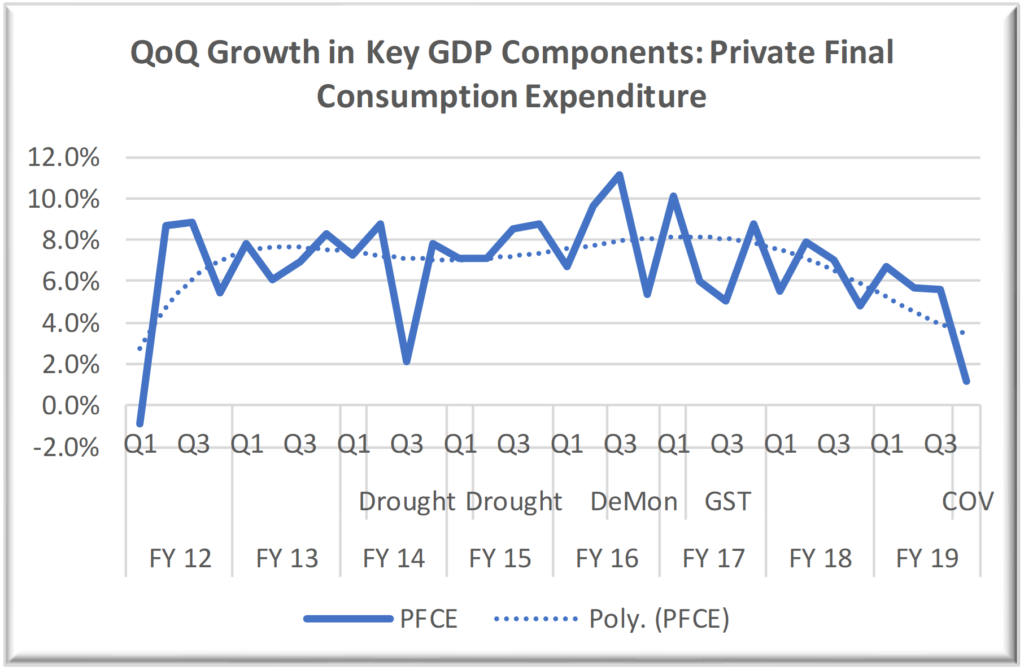

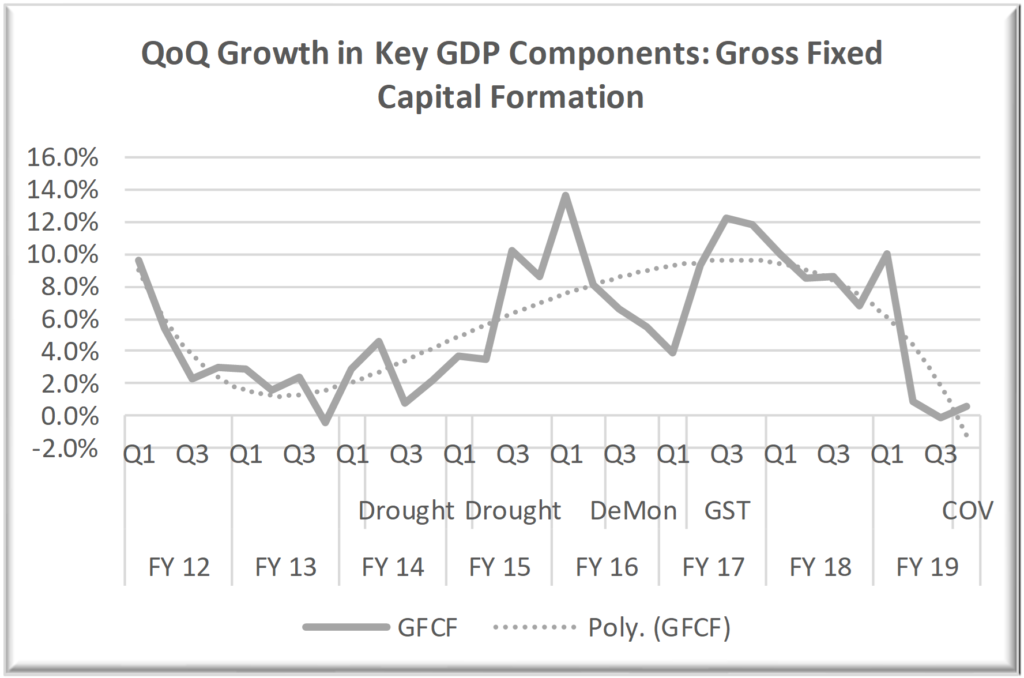

During the last few years, we have experienced a steady decline in quarterly growth in gross domestic product, which is the result of slowdown in growth of private consumption and unwillingness (inability too) of the large businesses, barring a few exceptions, to take risk and invest in manufacturing and infrastructure services for domestic and/or the global market. As we notice below, the growth in private consumption as well as capital formation has been trending down even before the pandemic.

The Indian business’ inability and/or willingness to invest and take risk has resulted in China, whose average per capita income is many times more than India, supplying low value-adding goods (consumption as well as capital) to India, i.e., a high-cost economy is supplying goods to a low-cost economy. For example, India imports about USD 10+ million worth of pens and pencils from China.

Government Employment is key to building the ‘Ability to Grow’ and ‘Willingness to take Risk’ in an Economy, where the organised private sector is not playing its role of providing opportunities for stable household earnings.

Since the government employees are expected to receive a stable fair wage that compensates for cost of living, they are best positioned to leverage (borrow) their earnings for increasing their consumption and the risk of investment. The government wage becomes the basis for wages in the private sector and thereby helps raise the level of earnings for everyone.[2]

We don’t have to fear a wage-led inflation, as the private sector is expected to be good at managing productivity through product and process innovation. Leveraging engineering and science knowledge, combined with ability to manage is key to profitability and not economy-wide low wages – the organised private sector is expected to do just that.

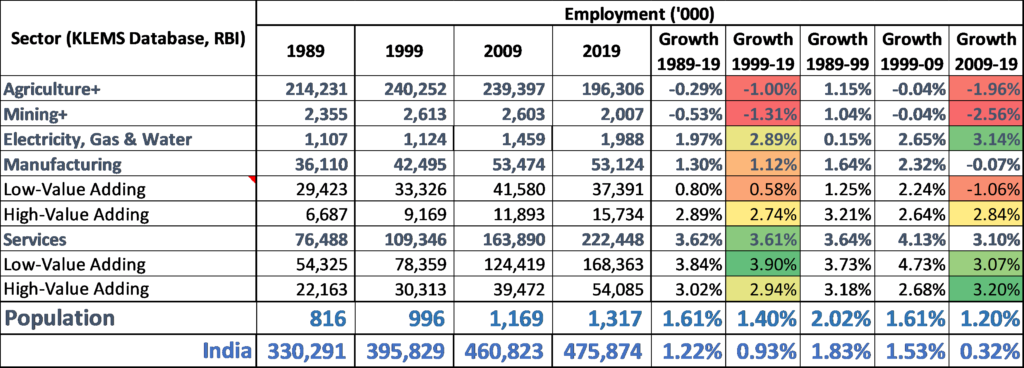

Growth in aggregate employment level has been lower than growth in population, particularly during the last decade

During the last two decades, the growth in employment at 0.93% (Organised as well as Unorganised) has been lower than growth in population at 1.40%. During the last decade (2009 to 2019), the growth in employment is at 0.32% against the growth in population of 1.2%.[3] It is, therefore, not surprising that consumption and investment growth has begun to slow down. Growth in employment between 1989 and 1999 was 1.83%, with the population growth being 2.02%.

We, of course, know that the pandemic has resulted in large job losses since 2020. The current situation is likely to be worse than what it has been during earlier years.

Indian government has been working to reduce the level of Public Sector employment since 1991 and the risk of employment and earnings is shifting to households

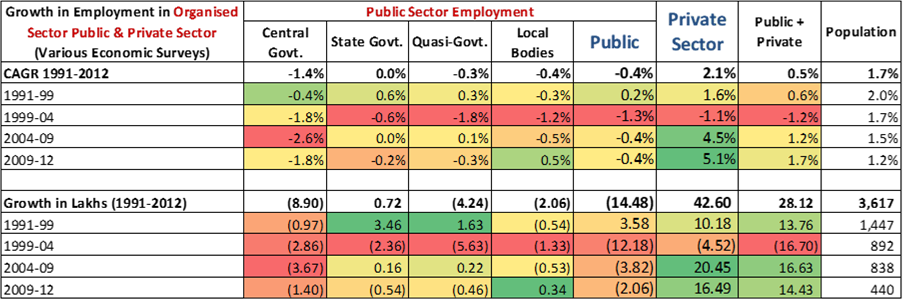

While the growth in aggregate employment is low at 0.93% (as presented in the table above), the growth in organised employment is, at best, poor at 0.50% between 1991 and 2012 – 2012 is the last year for which the data is available.

The Indian government, at all levels of governance, has been reducing the employment level, during the two decades for which data is available.[4]

India created just 28.12 lakhs (2.81 million) additional organised employment from 1991 to 2012, a period during which India’s population increased by 36.17 crore or 361.7 million. Table below is based on information from the annual Economic Survey.[5]

While the organised private sector had created 4.26 million jobs, the government shed 1.45 million jobs during that period. The central government has been shedding the largest number of jobs, among the various levels of government.

During the 1999-2004 period, the public as well as the organised private sector shed jobs. It took another 5 years (2004-09) to recover those losses. Since then, the government has continued to shed jobs, i.e., till 2012, the last year for which data is available.

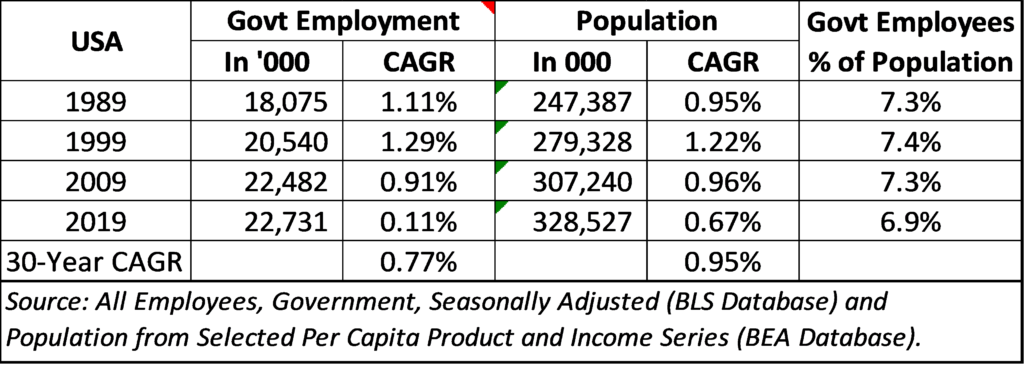

Even the US, the world largest economy has been maintaining a steady level of government employment for decades, except post the global financial crisis where the growth in government employment has been much lower than growth in the US population. While the US government employment has been ~7% of its population for decades, the Indian government employment was 1.45% (having fallen from 2.25% in 1990) of its population during 2012.

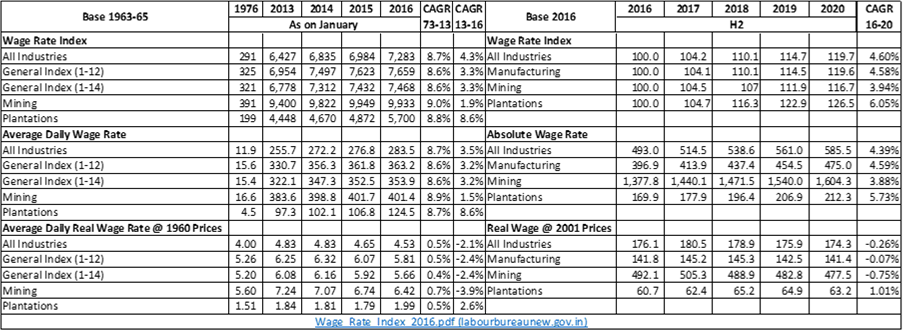

We also know that a large number of government employees are being hired on contract and their wages are far lower than what they would have received, had they been on permanent rolls. The private sector is doing that too. Consequently, the risk of employment and earnings has been shifting to households. At the same time, the entry level wages[6] have been stagnant and real wage growth is either negative or low for years.

Negative Real Wage Growth across sectors, combined with low growth in Employment Level, compromises an average Indian family’s ability to Consume and Invest

A review of growth in wages suggests that the real wage growth has been negative, particularly since 2013, except for plantation workers.

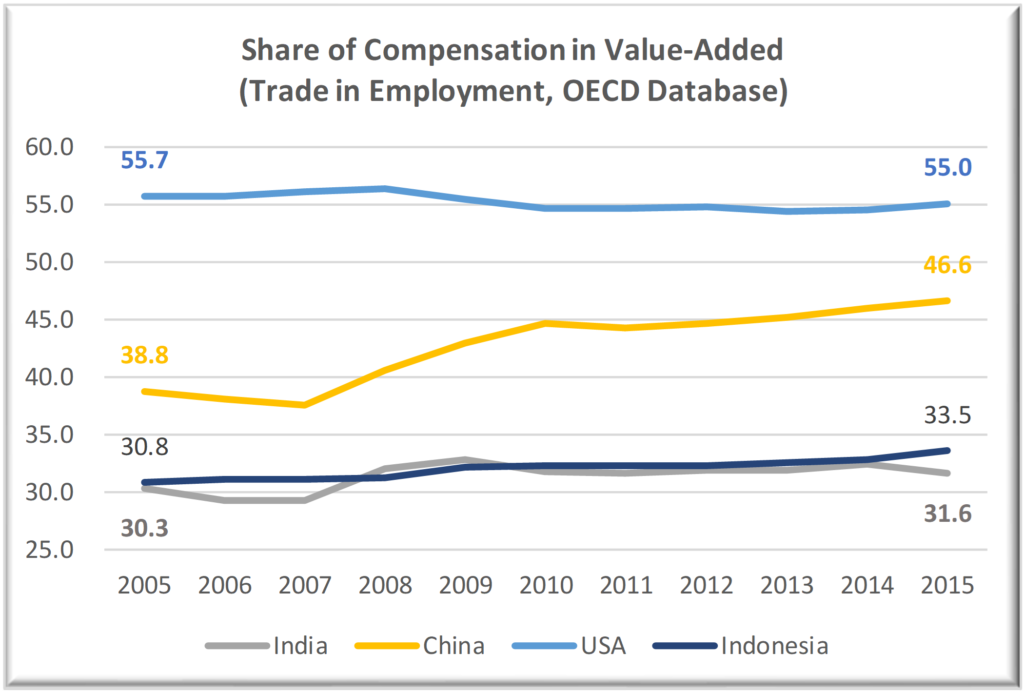

At the aggregate level, comparing with other large economies, the share of compensation in value-added for an average Indian worker is low and has been stagnant. During the same period, China’s average worker has received a much higher share, which implies a higher ability to spend and invest for an average Chinese worker.

Summary

As mentioned earlier, the most important determinant of economic progress is consistent growth in household and business earnings. The organised, government as well as the private, sector is expected to lead the way in providing quality employment. The private sector follows the government wage levels and leads the value creation activity through growth in productivity and investment in innovation.

The organised sector’s margins come from growth in productivity and better pricing as the demand for higher value-adding consumption goods and services increases with increasing real household earnings – creating a virtuous cycle of growth and prosperity. As observed above, India has not been able to build this virtuous relationship. The recent unrest among youth is a consequence of India’s inability to build the virtuous relationship between wage and profit growth.[7]

We, therefore, argue that India’s employment and wage growth crisis is an economic crisis that has been in the making for more than two decades. It has only got worse over the years.

We, therefore, need the Indian government, at levels, to recognise that the government job creation is as important as the organised private sector job creation, as the government wages provide a reference for private sector wage level.

Economic progress requires households to have stable earnings and businesses that are consistently profitable, and both are able to take risk and invest in their future. Hence, India needs to create greater number of organised sector jobs than it has been creating during the last two to three decades.

References

[1] Does the middle-income trap exist? | World Economic Forum (weforum.org) and 9781464809507_Spot06.pdf (worldbank.org)

[2] Currently, the National Level Floor Wage is INR 176 per day. Ministry of Labour and Employment, in its annual report for 2021-22, says the following: “On the basis of increase in the Consumer Price Index, the Central Government has revised the National Floor Level Minimum Wage from Rs. 160/-to Rs.176/-per day with effect from 01.06.2017.” The report also mentions the daily wage for highly skilled construction worker to be ranging from INR 724 to INR 864 and that for agriculture worker from INR 455 to INR 547, depending on the city.

[3] The Government of India has recently announced that it would create one million jobs during the next 18 months. Modi government to fill 10 lakh jobs in ministries and departments to tackle rising unemployment | Business Insider India

[4] It is probably more than two decades, as the organised sector employment data has not been made available since 2012.

[5] The Economic Survey has stopped updating the annual employment numbers since 2015. I have tried looking at other sources of information and have not been able to locate and updated time series. I would be happy to update the paper, if you could please point me to the latest data.

[6] Little change in salaries of entry-level IT jobs in India – The Economic Times (indiatimes.com), an article that mentions about the problem of oversupply in the IT Sector – the sector that has been creating better quality jobs for some time now. Job Series (Part 3): Freshers’ salary in IT sector stagnant for 7 years (moneycontrol.com), mentioning about lack of communication and technical skills and nature of wage stagnation.

[7] India gdp growth: India’s profit-to-GDP hits 4-year high, but best is yet to come – The Economic Times (indiatimes.com),