The Growth Paradox: Resolution through Change in ‘Frames for Choices’

Our inaugural Conclave last year had focused on making choices in a growth-constrained, information-age economy. Senior business and academic leaders had discussed about the structural and cyclical factors that are causing demand and supply constraints on economic growth; the impact of changes in digital technology on consumer preferences and industry value chains; evaluation of investment decisions, and; the role of leadership in a growth-constrained, information-age economy.

The consensus was that digital technology provides an opportunity for transformative changes in our personal, organisational and social life – changes that can improve the quality of life for the maximum proportion of our population. The realised value will depend on the investment we (individuals, organisations and the government) make in building capability to develop and leverage technology and create opportunities for wider participation in economic activity and social conversations – inclusiveness in its truest sense.

At the Conclave, we had discussed about the possibility of global growth getting desynchronised during 2018, implying possible head winds for growth in certain geographies. While our assessment was that the world economy will sustain the recovery witnessed during 2017, we had outlined a few structural constraints on growth, i.e., low population growth, aging population, low productivity growth, slow growth in household earnings, etc.

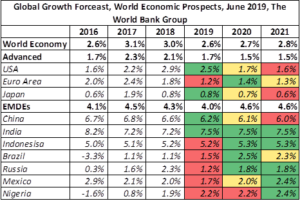

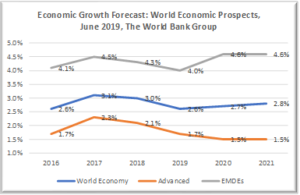

We now find ourselves at a stage where global growth has fallen sharply in the current year (2019) across all the major regions and is expected to recover only marginally during the next two years, and that too on the back of growth in relatively smaller economies, i.e., EMDEs like India, Indonesia, Russia, Mexico and Nigeria, Chart and Table 1.[1]

Chart 1

Table 1

Economic Growth: Near-Zero or Low-Interest Rates, Liquidity on Tap, but Subdued Investment and Softening Global Growth

The Global Economic Prospects (GEP) report states, “Global growth has continued to soften this year. Momentum remains weak and policy space is limited. A subdued recovery in investment growth in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) dampens potential growth prospects and hampers progress toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Risks remain firmly on the downside, including the possibility of escalating trade tensions, sharper-than-expected slowdowns in major economies, and renewed financial stress in EMDEs.”

GEP’s assertion about ‘subdued recovery in investment growth’ among EMDEs, a group that is expected to drive global growth, is based on the argument that the private as well as the public indebtedness in these economies has increased significantly[2] since the global financial crisis. Therefore, these economies don’t have a lot of room for credit-led investment growth. The report argues that “the current environment of low global interest rates and weak growth may appear to mitigate the concerns about elevated debt level”, but there is “no free lunch.” It also observes that “the private sector debt may shift onto government balance sheets during the financial crisis as governments provide support to private institutions in difficulty”.

Similarly, the Global Trends (NIC Report)[3] report suggests that the present choices (individual, organisational and public policy) have not really helped build a sustainable growth eco-system.

Specifically the NIC report mentions, “Debt-fueled economic growth in the United States, Europe, China, and Japan during the past several decades led to real-estate bubbles, unsustainable personal spending, price spikes for oil and other commodities—and, ultimately, in 2008, to massive financial crises in the United States and Europe that undercut economies worldwide. Anxious to stimulate greater growth, some central banks lowered interest rates to near—and even below—zero. They also attempted to boost recovery through quantitative easing, adding more than $11 trillion to the balance sheets of the central banks of China, the EU, Japan, and the United States between 2008 and 2016.”

The NIC report further states that the policy choices have “prevented further defaults of major financial institutions and enabled beleaguered European governments to borrow at low rates. They have not sparked strong economic growth, however, because they have not spurred governments, firms, or individuals to boost spending. Equally important, these efforts have not created incentives for banks to increase lending to support such spending, amid new prudential standards and near-zero or even negative inflation.”

In some sense, India is a classic case that reinforces the argument of ‘no free lunch’. The Indian financial sector is still struggling to recover from a credit-led investment growth[4] from 2005 and 2014 (a period characterised by double digit growth), the annual average growth in non-food gross bank credit was 29.3% between 2005 and 2009 and 16.3% from 2010 to 2014, with NBFC crisis[5] (with contagion effect on banking and mutual fund industry) being the latest episode in a long series of disclosures about non-performing assets by the banking system.

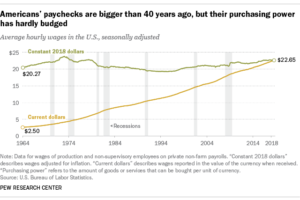

In our assessment, the low-rates and liquidity on tap will help only if the household earnings for a large part of the global population were growing. As we know, the growth in household earnings in many advanced countries has been tepid, at best. We also know that the education and health care cost inflation has been much higher than general inflation, requiring the advanced economies to spend ever increasing share of their resources on these services and the EMDE households (particularly lower and middle income households) are running the risk of being in a debt trap.

Not to mention the fact that housing has become unaffordable in many advanced as well as EMDEs. For example, the median House Price to Income (HPTI) ratio has worsened from 56.1 in March 2015 to 61.5 in March 2019. During the same period, the Loan to Income (LTI) ratio has worsened from 3 to 3.4, which was at 2.8 in 2009-10. All of this in a period of declining growth in house prices.[6]

We present the following charts (relating to the world’s biggest consumption-led economy – the US) to support our arguments. Charts 2 implies that average hourly real wage in the US has grown just by 0.20% per annum since 1964. During the early 1990s, the wage rate declined below USD 20, which was the level in 1964. It is still below the peak reached during the 1970s.

| Chart 2 implies an annual compound growth rate of 0.20%. |

Chart 2[7]

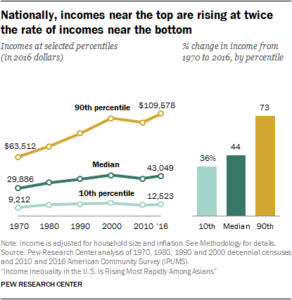

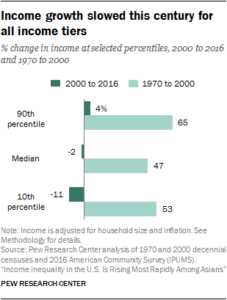

Chart 3 suggests that the growth in real income has been 1.19% for the 90th percentile, 0.80% for the median and 0.67% for the 10th percentile households.

Chart 3[8]

| Chart 3 implies “Lower the income, lower the growth rate.” |

Chart 4[9]

| Chart 4 implies a compound annual growth of 0.25%, -0.13% & -0.73% from 2000 to 2016 for each of the groups. |

| Chart 4 also implies a compound annual growth of 1.68%, 1.29% and 1.43% from 1970 to 2000 for each of the groups. |

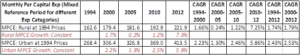

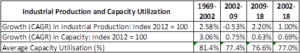

Equity of growth has not been very different even in the EMDEs. An analysis of monthly per capita expenditure in India, based on the National Sample Survey data, suggests that the growth in rural India has been lower than that in urban India and the differences have only increased since 1994, except during 2012-12, the latest period for which data is available. Table 2 below provides detailed information on consumption at current and constant prices. India does not have a reliable time series data on personal incomes.

Table 2

The NIC report further states that “Efforts by Beijing, for example, to stoke growth since 2008 have helped maintain oil and raw-materials markets, as well as the producers in Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East who supply them. Nonetheless, these markets have sagged with the realization that China’s growth—based largely on investment to boost industrial capacity—is unsustainable.”

In other words, China, the world’s biggest commodity consumer and the main driver of global growth over the last few decades, is not able to help the world rebuild the growth momentum.

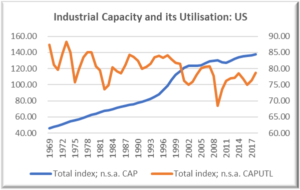

Chart 5 below suggests that even after a sharp recovery post the crisis, the industry capacity utilization in the US remains at the lowest level in the last 50 years. We also observe that the growth in capacity addition has also been at the lowest level in these 50 years (Table 3).

Chart 5[10]

Table 3

The average capacity utilization in India has crossed 75% level in just four quarters during the last 7 years. It has been between 72% to 74% in most quarters.[11]

As for the response in financial markets, the NIC report states that “In this low-rate, low-growth environment, investors have remained skittish. They have vacillated between seeking higher returns in emerging markets and seeking safe havens during periodic scares, providing only unreliable support for potential emerging-economy growth.”

In short, we now find that a credit-led investment and consumption growth is not sustainable, as low interest rates (near zero or negative rates in advanced economies and low-rates in EMDEs), nearly unlimited liquidity on tap and the government support by some of the largest economies of the world is not able to bring back the growth momentum witnessed during the pre-crisis period.

We therefore ask,

What do we do to accelerate household earnings and consumption growth that can use already available excess capacity and bring back investments without households, organisations and the government piling up forever more debt? While debt is an essential part of financing mix, the challenge is in identifying the threshold or inflection point beyond which the increased indebtedness will lower individual, organisation and the government’s ability to deal with uncertainty or invest for the long run. And we are not dead in the long run. Individual entities do (die), but the collectives (families) live on.

In other words,

- What conscious and deliberate choices (personal, organisational and public policy) would help households earn more and thereby spend and save more, a demand-led view of economic growth rather than a supply-led view?

- How do we get organisations to raise additional risk capital for investing in innovative value-creating products, services and solutions rather than rely on steroid (read debt) based financing strategy that uses leverage to boost returns through acquisitions and/or buy back of stock?

- How do we get the governments to support investment in economic and social infrastructure that reduces the cost of living without compromising the quality of life for urban population and creates economic opportunities in urban, semi-urban and rural areas, thereby reducing the need for building mega cities where the migrant population is expected to come and find work?

And what we don’t ask is – when will the reduction in interest rates or the cost of finance spur investment growth?

Digital Technology: Ability to transform lives comes with inequitably distributed cost of transition in a world where ‘data is new oil’[12]

We are seeing a large amount of investment in development and deployment of digital technology across a wide spectrum of economic and social activities. IDC estimates that the global private and public spend on digital transformation in 2019 to be USD 1.18 trillion, an increase of 17.9% over 2018. [13] It expects the spend to be growing @ about 20% till 2022, with the US and China being the two biggest spenders and contributing nearly half of the total spend.

While the conversations around the impact of technology are enjoying a very high mindshare, we are yet to see the value from adoption of digital technologies accruing at a scale that improves lives for large number of people, which compensates for the costs that the adoption of technology is imposing on people whose livelihood is being adversely impact by the change. Anecdotal evidence in form of lay-off announcements suggests that we are probably at a stage where the cost associated with transition are still substantially outweighing the current benefits.

Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo[14] suggest that “one more robot per thousand workers reduces the employment to population ratio by about 0.18-0.34 percentage points and wages by 0.25-0.5 percent.” They also quote other studies which mention “that the automation of a range of low-skill and medium-skill occupations has contributed to wage inequality and employment polarization (e.g., Autor, Levy and Murnane, 2003; Goos and Manning, 2007; Michaels, Natraj and Van Reenen, 2014).”

The NIC report states, “Technology will continue to empower individuals, small groups, corporations, and states, as well as accelerate the pace of change and spawn new complex challenges, discontinuities, and tensions. In particular, the development and deployment of advanced information communication technologies (ICT), AI, new materials and manufacturing capabilities from robotics to automation, advances in biotechnology, and unconventional energy sources will disrupt labor markets; alter health, energy, and transportation systems; and transform economic development. They will also raise fundamental questions about what it means to be human.”

A ‘canvassing of experts’ study[15] by Pew Research Center and Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center, an anonymous professor at one of the world’s leading technological universities who is well-known for several decades of research into human-computer interaction wrote, “Deterioration in privacy; slicing and dicing of identity for sale; identification of individuals as targets for political messaging. I don’t see the institutions growing that will bring this under control. I don’t see corporations taking sufficient responsibility for these issues.”

In the same Pew Research and the Internet Center study Rob Reich, professor of political science at Stanford University, said, “If the baseline for making a projection about the next today is the current level of benefit/harm of digital life, then I am willing to express a confident judgment that the next decade will bring a net harm to people’s well-being. The massive and undeniable benefits of digital life – access to knowledge and culture – have been mostly realized. The harms have begun to come into view just over the past few years, and the trend line is moving consistently in a negative direction. I am mainly worried about corporate and governmental power to surveil users (attendant loss of privacy and security), about the degraded public sphere and its new corporate owners that care not much for sustaining democratic governance.”

While there is no denying that the advances in technology will create significant amount of value in the long-run, we know that the people who will benefit in the long-run are not the same as those who will bear the cost of transition that helps generate these benefits.

Our questions therefore are:

- What kind of investments (in getting future ready) do individuals and households need to make for coping up with digital transformation currently under way? How do they meet the challenges arising (e.g., loss of earnings, raising of capital for investment) from the transition?

- How does an organisation engage different stakeholders (customers, employees, suppliers, shareholders and the local community) allowing it to deal with the challenge of transition and deliver value that digital transformation can potentially help create?

- How do we reduce and finance the cost of transition to the new information-age, particularly for those who are the most disadvantaged?

- What role does the government have in (e.g., part financing the cost of transition and defining the nature of regulation) helping the society deal with these transformational changes?

And the question that we don’t ask is – how many job losses will the adoption of technology result in or how many jobs will it create? The reason we don’t ask this question is that any such estimate, sitting today, requires us to predict the future. We can foresee, but not predict.

Changing Nature of Work and Organisation and declining Trust in Institutions in a Low-Growth, Digitally Connected World

It is expected that the population growth rate will continue to slow down. However, the world population will continue to be large, median age will increase and an increasing proportion of population will live in urban centres with population in excess of 10 million. While the advanced economies will need to find people to fill available jobs, the emerging and developing economies will need to find jobs for millions of their young. We will need to create hundreds of million new jobs, but these jobs will not necessarily be the same as in the past.

Over the last few years, we have also seen the nature of contract between a hirer and the hired change significantly. A Deloitte Survey[16] suggests that the employers are likely to increase their dependence on “contract, freelance, and gig workers over the next few years.” The Survey expects that the alternative work arrangements are likely to become more widespread, requiring organisations to increase their engagement with external stakeholders and seek greater degree of collaboration within and outside the firm.

As we know, migration of labour across borders and increased woman participation in labour force, along with automation are the possible solutions, which implies that we will have to prepare ourselves for a diverse labour force, with ever-increasing human-machine interfaces.

But, all of this will have to happen in an environment where the current sentiment about migration and automation is not necessarily positive. And at a time when the jobs that are likely to be available in future will be very different from the ones that are currently available. We expect the nature of work as well as the nature of organisation to change. Risks and uncertainty that individuals are expected to face will be different from that we currently face. Consequently, we will need to redefine the compensation and incentive structure, which allows for equitable risk-sharing arrangement among employees and the employers. We expect the idea of an employee or an employer itself to be very different than what it is now.

One of the most important current challenges is that the pre-crisis high growth has not necessarily built or enhanced the ability to deal with an uncertain, low-growth environment, largely reflected in an increase in income inequalities (within advanced as well as emerging and developing economies) and stagnating median real incomes (particularly in advanced economies). While an increasing number of people are investing in education, the education is coming at greater cost to individuals (in most countries where it is in the private sector) and being financed through increasing amount of debt.

At the same time, the rapidly growing urbanisation requires increased investment in economic as well as social infrastructure. In economies, where the public-sector indebtedness is high, the private sector investment needs to fill the required gap. On the other hand, where the private sector is heavily indebted, the public-sector must be a major investor. All of this is taking place at a time, when the global capital is chasing absolute returns in an uncertain, low-growth environment.

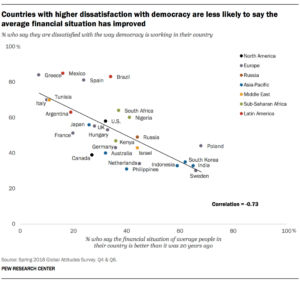

As expected, one of the consequences of increasing inequity in a digitally connected, urban landscape has been an increase in dissatisfaction with the current state of institutions. Many of these societies are becoming inward looking and the politicians are exploiting the situation by resorting to populism as the basis for public discourse. In short, we have a situation where the dissatisfaction with current economic situation is high, which is, in turn, resulting in the dissatisfaction with the current political order. Chart 6 and Chart 7, drawn from Pew Research Center studies, provide insightful information about nature current dissatisfaction.

Chart 6[17]

| Chart 6 implies “Lower the dissatisfaction with democracy, more +ve is the view that current economic situation is better than in the past.” |

Chart 7[18]

| Chart 7 implies that democracy is not working well and the situation has worsened in a year’s time itself. |

The NIC report states that populism characterised by “a suspicion and hostility toward elites, mainstream politics, and established institutions…reflects rejection of the economic effects of globalization and frustration with the responses of political and economic elites to the public’s concerns.”

The report goes on to speculate, “a more interconnected world will continue to increase—rather than reduce—differences over ideas and identities…..The increasingly segregated information and media environment will harden identities—both through algorithms that provide customized searches and personally styled social media, as well as through deliberate shaping efforts by organizations, governments, and thought leaders.”

In short, the changing nature of work, work contract and general dissatisfaction with the current economic, governance and social institutions in an increasingly urbanising world implies that the rules of engagement in personal, organisational and social context may have to be different from what they were in the past.

Our questions therefore are:

- Given the evolving nature of work and the work contract will the current way of organising (matrix relationships in a hierarchy-based responsibility structure) serve the purpose? If not, what is the possible alternative structure or structures?

- What kind of compensation and incentive structure will allow individuals and organisations to share risk and returns equitably and allow them to invest in building capability in an uncertain, low-growth environment in a society in transition?

- What is the role of organisational leadership in this new world? Do we need heroic leaders, or would the collaborative leaders be more effective?

- What is the role of trust among different stakeholders in personal, organisational and social context? Do we expect trust to play an increasing role in the future? If yes, how do we build trust in personal, organisational and social relationship?

The Growth Paradox: Resolution through change in ‘Frames for Choices’

The NIC report characterises the current and the emerging situation to be a ‘paradox of progress’. It argues, “Our story of the future begins and ends with a paradox: The same global trends suggesting a dark and difficult near future, despite the progress of recent decades, also bear within them opportunities for choices that yield more hopeful, secure futures.” It is an indeed a paradox.

We see the current state of paradox to have resulted from our inability to identify the inflection points when a given set of premises and frames stopped being relevant to the context. That is, a market-based economic system founded on the principles of private enterprise; free movement of goods, people and capital; meritocracy, and; self-regulation, combined with a liberal democratic socio-political system has had only limited success. It has delivered economic well-being for some and not others.

The choices, based on the above premises, have failed to deliver to the promise of building a just and equitable society where the natural rate of growth is high and the need for steroids (near-zero or low-interest rates, unlimited liquidity on tap, poorly designed, ineffective subsidy programmes, lobby-driven policy choices, etc.) is low.

The current set of dominant frames in personal, organisation and public context are:

- Personal, it pays to educate oneself and one’s children even if it involves borrowing as the skills and knowledge acquired through education will help increase the probability of employment or success in any other economic activity and earning an income that will compensate for risk and the cost of investment;

- Organisational, growth is a cyclical phenomenon and a strategy that can help survive the low of the cycle through restructuring and/or help lead consolidation of industry through mergers and acquisitions is worth its while, as the natural growth in demand will come back sooner or later. We just need the cost of finance to be lower, with adequate liquidity in the interim, and;

- Public policy, a merit-based, competitive economic and social system is self-correcting and the excesses of an individual or a firm are a price worth paying, as the actions of other individuals and firms will weed out inefficiency, resulting in greater good and survival of the fittest in the long run. The government’s role is limited to creating a level-playing field, keeping a watch on systemic risks and internal and the external security. Markets and democratic institutions will take care of the rest.

Currently, the choices made using these frames don’t seem to be effective. Education pays, but not for everyone and not all the time, as the needs of the future are different from those of the present, and the teachers or the education administration (for that matter most of us) don’t have the ability to predict the future and design education programmes of the future. Low-cost finance, with liquidity on tap, does not necessarily give us the ability to wait out the low of an economic cycle, as the natural growth in demand is taking far longer to come by. The level playing field is not all that levelled, as the real income for a vast majority of people are stagnant and household indebtedness in on the increase.

Our premise is that the current frames for choices are grounded in inequitable risk-sharing arrangements. The cost of living is growing at the rates faster than earnings in most urban centres; the work contracts are getting shorter; share of variable compensation has increased to an extent that it now forms the bulk of an individual’s compensation; defined benefit-based social security system is becoming defining contribution-based system where significant share of investment is in risky financial assets; while the interest rate are nearly zero, the risk capital providers expect a double digit return – we are, of course, not talking about private equity investors whose return expectations are anywhere between 20-40%; interest is taxed at regular rates for the retired but carried interest is treated for private equity investors or managers is not; cost arbitrage-based global trade in goods and services depresses wages in advanced economies where the cost of living is high and pushes up the cost living in the producing economies (EMDEs) where the wages don’t necessarily keep pace with the increases in cost of living, and so on. We, in way, have a large set of contradictions to deal with.

We have created a socio-economic system where the benefits are private for a small percentage of people, but the costs their actions impose on others are not, e.g., unprecedented bail outs of large banks whose actions resulted in layoffs in businesses that had nothing to do with banking. Dissatisfaction with economic, financial, political and social institutions is a natural consequence of a system where risk-return and cost-benefits trade-offs are not wisely made.

In view of our discussion in this note, we argue that there is a need to create frames for choices, where risks are shared equitably, i.e., they are transferred to people who have the ability to bear and manage them; compensation for taking risk is determined objectively and fairly, and; the risks that individuals are not able to take are manged by the society through organisational and public policy choices.

Our argument is based on the premise that organisation and the government are the institutions that are meant to serve the individual purpose (including the last the person in the queue) and not the other way around.

Our conversations at the Conclave are designed to identify the frames that can guide our personal, organisational and public choices in a way that allows us to build risk-sharing arrangements that are objectively and fairly structured, help restore the trust our institutions of the past enjoyed and raise the natural rate of growth. Thus, reduce the need for frequent use of steroids.

Notes

[1] World Economic Prospects: Heightened Tensions, Subdued Investment, June 2019, World Bank Group.

[2] The average EMDE debt stands at 169% of GDP in 2018, up from 98% in 2007. It is at a record 107% of GDP even after excluding China.

[3] Global Trends: Paradox of Progress, January 2017, The National Intelligence Council, United States.

[4] Gross Domestic Capital Formation (GDCF) grew at an annually compounded rate of 15.4% from 2004 to 2014 and the bank credit at 22.5%. Since then the bank credit growth has fallen to 8.4% (March 2014 to March 2018) and the GDCF to 5.7%.

[5] Even a quick review of the Section on Network of the Financial System in the Financial Stability Report, Issue No. 18, by the Reserve Bank of India, suggests that the lightly regulated segments (AMCs, NBFCs and HFCs) of the financial system were potentially adding to the systemic risk, as they were becoming the shadow banks for stressed sectors like the real estate, medium and small businesses, etc.

[6] Residential Asset Price Monitoring Survey, July 11, 2019 and Recent Trends in Residential Property Prices in Indian: An Exploration using Housing Loan Data, May 7, 2015, Reserve Bank of India.

[7] For most U.S. workers, real wages have barely budged in decades, Drew DeSilver, August 7, 2018, Pew Research Center @ https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/08/07/for-most-us-workers-real-wages-have-barely-budged-for-decades/

[8] Income Inequality in the US is rising most rapidly among Asians, Rakesh Kochhar and Anthony Cilluffo, July 12, 2018, Pew Research Center @ https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/07/12/income-inequality-in-the-u-s-is-rising-most-rapidly-among-asians/

[9] Income Inequality in the US is rising most rapidly among Asians, Rakesh Kochhar and Anthony Cilluffo, July 12, 2018, Pew Research Center @ https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/07/12/income-inequality-in-the-u-s-is-rising-most-rapidly-among-asians/

[10] Table 11 Historical Statistics for Industrial Production, Capacity, and Utilization: Total Industry @ https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/table11.htm

[11] RBI’s quarterly Order Book, Inventories and Capacity Utilisation Survey.

[12] The World’s Most Value Resource is no longer Oil, but Data, May 6, 2017, The Economist.

[13] Businesses Will Spend Nearly $1.2 Trillion on Digital Transformation This Year as They Seek an Edge in the Digital Economy, Michael Shirer and Eileen Smith, IDC @ https://www.idc.com/getdoc.jsp?containerId=prUS45027419

[14] Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets, Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, NBER Working Paper No. 23285, March 2017.

[15] The future of Well-being a tech-saturated world, Janna Anderson and Lee Rainie, April 17, 2018, Pew Research Center, @ https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/04/17/concerns-about-the-future-of-peoples-well-being/

[16] The Rise of the Social Enterprise: 2018 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends

[17] Dissatisfaction with performance of democracy is common in many nations, Richard Wike, Laura Silver and Alexandra Castillo, April 29, 2019, Pew Research Center @ https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/31/the-countries-where-people-are-most-dissatisfied-with-how-democracy-is-working/

[18] In many countries, dissatisfaction with democracy is tied to views about economic conditions, personal rights, Alexandra Castillo, Christine Huang and Laura Silver, April 29, 2019, Pew Research Center @ https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/29/in-many-countries-dissatisfaction-with-democracy-is-tied-to-views-about-economic-conditions-personal-rights/