Nature and Scope of Digital Organizations

Defining digital technologies – and by implication digital organizations – is an ambitious task, because they are ubiquitous, dynamic, exist in varied forms, used differently for various purposes, and keep evolving with new technologies every few years. This variety and constantly evolving nature make it difficult to define digital technologies in a way that is future-proof and useful to develop management principles for a digital organization.

The field is rich with various definitions as to what is meant by digital itself with some leaders viewing it as an upgraded term for IT, whilst few others consider it as applying to sales, customer relations, or marketing in specific ways[1]. This fuzziness in the foundational term “digital” in turn influences the meaning and intent of other derived terms, such as digital strategies, digital transformation, digital technologies, artificial Intelligence, and digital organizations. A leader who understands digital as an upgraded IT will have very different perception of digital transformation from a leader, who understands it as using cloud-based platforms or another leader, who understands it as an effort to use digital technologies to implement a new business model. The benefits, risks, resources, change management and employee involvement will be very different, as their implicit definitions of digital transformation are different.

There is, however, one common denominator in most forms of digital technologies irrespective of their variety, namely, their main currency is information and data. Most digital technologies trade-in information and data, whether they connect, compute, facilitate interactions, model or predict. Digital technologies also either by themselves or through them enable other digital resources, such as APIs, RPA, algorithms, and virtual assistants (Note: In this paper, information and data are used interchangeably, though there are differences between them).

To be sure, organizations could have had data previously, but where digital technologies make the difference is they enable access to them, and subsequent use and processing at scale at a very low cost. Digital technologies proved to be a game-changer with respect to scale, cost, speed and convenience to make data available to firms for their use. Digital technologies make it possible to capture, combine, analyse, integrate, distribute information in very cost-effective, scalable and innovative ways at various levels of granularity irrespective of time and geographical constraints. They also enable firms to move away from legacy, set, and historical data to various forms of previously inaccessible or expensively available data. Examples include real-time, interactive data, qualitative and proprietary models that retrieve and use data related to machines, people, economy, and consumers behaviour. (Note: Whilst data and information are specifically called out as a common denominator of digital technologies, a broader term is digital resources, which could include APIs, RPAs, Cloud, microservices, etc., and also interchangeably used in this paper.)

In doing so, digital technologies enable informationalization of business resources and operations, industrialization of information (at scale and low cost), and innovation in strategies, business models, products and services, and more. Though it depends on the firm, the level of complexity and potential to create value increases as a firm moves from the lower end (informationalization) to the higher end (innovation).

1) Digital Resources and “Economics of Information[2]”

The digitalization and informationalization of business activities merit additional mention here, because it changes the “economics of information” [3], and in doing so, sets the stage for industrialization (of information) and innovation.

Historically, information was carried by physical things, and therefore its’ speed, timeliness and flexibility were subject to the constraints of physical things. For example, shipment status can be known at set points only, where infrastructure to do so existed. Digital technologies, however, enable information to travel by itself (on connected devices, people, things, etc), and, in the process “the traditional link between the flow of product-related information and the flow of the product itself, between the economics of information and the economics of the things can be broken … it offers to unbundle the information from its physical carrier”[4]. In doing so, digital technologies break the traditional trade-offs between information richness (amount, customization, interactivity) and reach (number of audiences, or units engaged). Traditionally, information richness was limited to limited audiences, as customization and interactions required dedicated resources and costs. With digital technologies, the cost of customisation drops significantly and detailed information is available without significant additional resources. In other words, the economics of information/data is changed. A good example of this is Internet of Things (IoT), where machine (or a mechanical parts’) performance can be known remotely in real-time through sensors, and preventive measure can be taken saving costs and time. There are already business models, which leverage on this, and offer success or performance as a service.

Industralization of information (or data) at low cost and scale, when powered with analytics, allow not only market and business analysis to uncover (good and not-so-good) trends, but also optimize resources in real-time to make the value-chains more resilient and efficient. The large troves of data also sets the stage for machine learning and deep learning enabling, in theory, everything from new (cheaper and faster) drug discovery and personalised medicines to popular TV serials and chatbots.

Innovation is the most difficult frontier in the information value-chain, as it depends integrating insights available through industrialization of information with subjective, creative and philosophical assessment on building “new” value often in uncharted markets, economy and social well-being. This requires integration of information (and data) enabled by digital technologies with what technologies are there for. It requires asking questions on how to get most from technologies in creative, ethical and responsible ways.

2) Digital as a Strategic Resource

The combined effect of digital technologies in enabling informationalization, industrialization and innovation (through information and data) effectively converts information (or data) into a strategic resource that is next in line with other factors of production in traditional economics, such as capital, land and machinery, Human Resources, and entrepreneurship. As Porter and Heppelmann[5] noted in the context of Internet of Things (IoT), “Data now stands on par with people, technology, and capital as a core asset of the corporation and in many businesses is perhaps becoming the decisive asset.”

Whilst information and data are most familiar and recognized resources enabled by digital technologies, advances in digital technologies have given rise to their own set of resources, which vary in complexity and usefulness, but increasingly being deployed to add value to organizations and its’ stakeholders. Examples of such digital resources include digital tools, such as APIs, RPA (Robotics Process Automation), micro-services, chat-bots, and digital technologies themselves. Digital technologies along with its’ data and information, and various digital tools that they enable can be considered a separate resource (namely, “digital resource”) next in line with traditional resources, such as capital, land & machinery, and human resources.

Just as each factor of production has its own specific features, digital resources, too, as a resource, have unique features. These unique features have implications for market power, nature of competition, strategy, leadership and culture, human resources and ethics.

Our existing organizational templates, however, are premised on “traditional” economic factors of productions (land, labour, plant and machinery, capital) and predictable and stable business environment.

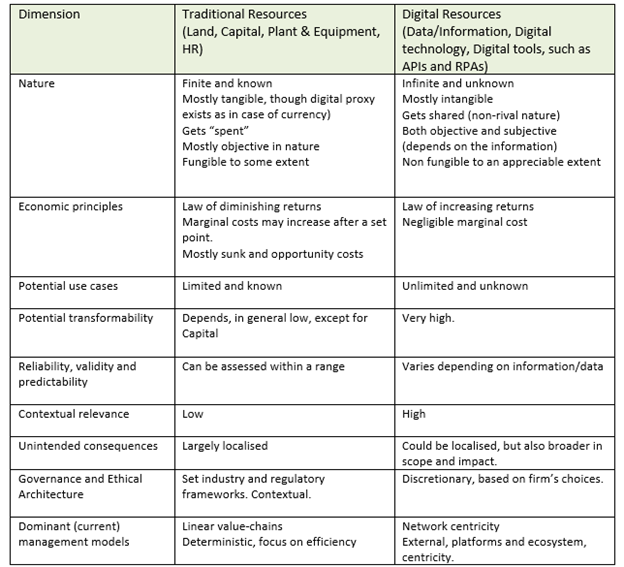

The table below maps the general differences (Note: they are not intended to be precise, but provide a general direction in thinking).

Table 1: General differences between “Traditional resources” and “Digital Resources”

(Note: Expanded comparison is available at the end of paper-set as additional information.)

The above table suggests that “traditional resources” are finite, subject to controlled accessibility, predictability within a given range, relatively static (do not mutate or multiple variants at the same time), objective, get “used”, depreciated, or “spent”, and exists at pre-set levels of granularity. It therefore makes efficient use of resources a priority through long term plans and detailed operating procedures, and command and control structure.

The “digital resources” are, in theory, infinite, flexible, available broadly, both objective and subjective in nature, dynamic (can change quickly), and exist at varying level of granularity. They are also more contextual, and therefore their relevance and use depend on how they are understood, embedded in various organizational systems and social context, and managed and governed.

Given significant differences between traditional and digital resources, it follows at a conceptual level that digital organizations may have different – or additional – strategy, cultural and leadership implications.

3) New compact between information, uncertainty and value

The informationalisation, industrialization (of information) and innovation (through data) enables a new compact between information, cost/time, uncertainty and value. In theory, a new business proposition (new business model or a new strategy – a distinction between the two is outside the scope of this paper) is generated when information enabled through digital technologies leads to a product, service, or a feature that could materially change the cost, time or uncertainty related to a product or service. Common examples of uncertainty include performance, maintenance, downtime, and availability of a service, when needed.

This compact, enabled by digital resources (including the information and data), becomes feasible and sometimes more powerful due to the following features of information/data, which are in most cases also applicable to other digital resources (such as APIs and RPAs).

a) Lower marginal costs

Digital technologies enable firms to benefit from low (or negligible) marginal costs (in production and distribution of digital goods, or in services offered digitally). Though lower marginal costs with rising production also exist (within a range) in manufacturing / product industries due to experience curve and economies of scale, the scale and level of lower marginal costs (almost negligible) puts digital goods in a different category. As an example, the marginal cost of producing and distributing 100th copy of a digital book is lower than the marginal cost of producing and distributing 100th copy of a physical book. This means that firms that deal in informational goods and services predominantly (as in digital music, or messaging app) will have significant cost advantage over their analog competitors.

b) Lower transaction costs

Digital technologies enable lower transaction costs, and this feature creates both challenges and opportunities for businesses depending on their existing business model. Lower transaction costs may lead to disintermediation (as in removal of middlemen), unbundling of specific activities (as in off-shoring and outsourcing, repair services, etc), and re-configuration of value-chains (as in Fin-Tech and on-line entertainment industry). In addition, digital technologies reduce discovery costs, which allow markets to exist for very specialist products and services (say, a rare book), which itself is a form of consumer surplus.

c) Non-rival nature of information

Non-rival information refers to information goods being available even after it is shared or distributed to others for use, unlike physical goods, which, once given, do not exist with the seller or the producer anymore. The non-rival nature of information (along with lower marginal and transaction costs) has important implications, such as giving rise to network effects and making businesses scalable in a short period of time. In other contexts, it could also create risks, such as use of intellectual property and copy-cat digital products and services.

d) Flexibility and connectivity

When compared with other “traditional” and physical resources, information is fluid, flexible, both subjective and objective in nature, inexpensive to transmit and duplicate, and lacks definite boundaries. Unlike physical and capital resources, which exist in whole units and not easily subject to either fractionalisation or unlimited scaling-up, information can be aggregated, disaggregated, pooled, fractionalized, scaled up and used at varying levels of granularity reducing uncertainty and giving rise to new business models. Shared car-riding, where a full car ride is fractionalized at an individual ride level creates value for consumer through cheaper cost. As an example, it is noted[6] that a ride-sharing is 40% cheaper than a regular cab for a 5-mile trip into Los Angles.

Information does not have hard limits on its’ scope to give it an absolute wholeness. It also lacks any natural constraints that preclude its integration or connectivity with information from different domains. Since information is a meta-resource (all other traditional resources information overlay that makes them more useful), these are important considerations, as they mean that various types of information can be aggregated and combined, often in new and innovative ways, to identify new business models and customer value propositions, which were not previously possible.

As an example, US based agriculture firm, Deere, offers innovative value to its customers (farmers) in the form of precision agriculture through outfitting its “products with automation, telematics, computer vision, GPS and sensors”[7] that allow the action (spraying of pesticides, etc) only when it is needed, based on data obtained from various sources (domains), which is then analysed with its’ algorithms to make prediction (such as whether a particular patch is a pest that needs to be sprayed upon).

e) Time-shifts and innovation

Digital technologies enable both synchronous and asynchronous use of information at scale.

The ability of digital technologies to release time-constraints on when, how, what and where information is available and consumed allows innovative value propositions, lower costs, flexibility, and, importantly, enables a new strategic compact between information and time leading to uncertainty reduction and new business models. For example, in many industries, ability to track real-time information, as in medicines and on-tracking of delivery, could be an advantage, whilst in other industries, as in entertainment and online education, asynchronous production and consumption enable new consumer value and market opportunities.

The ability to change the compact between time, information and consumer value is provided by one of the consumer credit products of Deutsche bank in Germany. “AI makes a real-time decision on whether or not to extend a loan to a customer as the customer is filling out the loan application. “This has generated a lot of interest among consumers,” … so much that, for that specific product, loan issuance shot up 10- to 15-fold in eight months … (Dasgupta’s theory on why: In Germany, an individual’s credit rating is damaged by applying for a loan but not receiving it. Deutsche Bank’s new AI solution removes that risk for customers by telling them whether or not they will be approved for a given amount before they hit “apply.” The largest gains haven’t come from better serving those customers who would have applied for loans anyway. Rather, the benefit comes from reaching those who would not have applied in the first place.”[8]

4) Market-Place Imperatives of Digital Technologies

The above discussion covers features of information /data (and other digital resources) that allow them to be different from other resources (say, land, or capital). When resources are available at scale at a cheap cost, it changes the compact between information, time, cost and strategy and in the process enables new sources of value-creation and business models. It is also suggested that information is a meta-resource, as other resources have information component in them (say, how efficiently a machine is working, or how much working capital is needed). To the extent, digital technologies are usefully and responsibly employed, it makes other resources also more productive and, in the process, adds provides another boost to the performance.

The potential of digital technologies through informationization, industrialization (of information) and innovation, however, requires organizational effort in strategy, culture, leadership and HR practices. That this is not easy is evidenced by few survey findings cited at the beginning of this paper. Organizations, however, do not have an absolute choice in the use of digital technologies, because whether or not they use it, it is very likely that their competitors – sometimes from other industries and eco-systems –use them, and impact an organization in competitive, strategic and financial terms. This leads to another premise of this paper – organizations may have more choice in how they use digital technologies than whether or not to use them in the first place.

When digital technologies are used in the market-place, the features of information /data (such as low marginal and transaction costs, network effects, etc.) start changing the market-place and competitive landscape in ways that are different from, when the competition is through traditional resources. A set of such considerations are discussed below:

a) Power law

A combination of the lower marginal, transaction and discovery costs leads to cost efficiencies, but also to changes in the nature of market place through the application of power law. Power law, or Pareto curve, describes a market (or a phenomenon) where a small number of actors (sellers) have disproportionate impact (sales). Power law has fat tails, scale invariant, and found to represent the sales distribution of information products, such as books, DVDs, and apps[9]. Power law happens because information products have low (or negligible) marginal costs and therefore production and distribution can be scaled up cheaply in a short period of time.

This phenomenon has important implications, as it gives rise to strategic behaviours guided by winner-takes all mentality, creation of entry barriers, and monopoly concerns. Research at Mckinsey shows that in terms of economic profit distribution, power curve has been getting steeper and “characterised by big winners and losers at the top and bottom, respectively”[10]. Power curve also leads to a herd-mentality to build scale with indirect subsidies and not so ethically well-tested market practices (as shown by the Uber example). Indirectly, but not insignificantly, it leads to superstar economy and superstar culture, and, as many observers argued to creating potential inequities in the society, as information and algorithms that it engenders are used to serve narrow interests of profit maximisation.

b) Long-tail markets

Digital technologies by lowering discovery and transaction costs facilitate the building of, and activity in, long-tailed markets. Long tails refer to the probability of extreme events being much greater than is possible in a normal distribution, and its business translation in this context refers to making the markets for niche and specialist products/ services bigger, accessible and more efficient.

Digital technologies through platforms and other communication means (on-line reviews, recommendations, communities, etc) enable a larger demand – and market – for various niche products and services, which otherwise would be uneconomical, because of overheads required to address low demand and sustain a niche business. It can be argued that a platform like AirBnB is in fact a collection of niche temporary accommodations, not otherwise possible to access without digital technologies. Other examples include availability of rare books, outdated products, and specialist appliances. It can be argued that by facilitating activity in long-tail markets, digital economy enables a “discovery” economy, and provides a balancing force to the winner-takes-all economy.

c) Network effects and inter-connectedness

One of the main – and many would argue the most important – features of digital technologies is that they enable network effects, i.e., they make a product or service more valuable as more users are engaged in it. Network effects could be positive or negative. They play an important role in the viability and success of business models that rely on platforms and eco-systems. Bigger network means access to bigger market, and also significantly more data that can be used both for operational and strategic purposes.

Network effects also increase the interconnectedness in the market place and economy. This inter-connectedness has both upside (it allows greater access to collaborate and provide services) and downside (the weakest link could lead to the failure of the system due to inter-connectedness). Interconnectedness due to algorithms and automated systems could also make systems less transparent and add to opacity, and thus compromise governance and healthy practices, as the experience of Facebook shows. Finally, interconnectedness makes predictions – and therefore detailed planning – difficult, as the outcome depends on the behaviour of multiple entities with different motives, strategies and ethical thresholds.

This was in evidence during the financial crisis of 2008, when Lehman Brother’s failure precipitated an almost collapse of the financial system and led to a special TARP program, as the financial system was very inter-connected.

d) Innovative business models

It is increasingly being argued that digital technologies have blurred the traditional industry boundaries, and that the real competition is now between platforms and eco-systems. Digital technologies have played an important role in raising the profile of business models that are platform and eco-system centric. Business model innovation however continues to be a hot area of business research, and digital technologies are enabling innovative business models not only in information rich industries, and also in industries that are typically seen as capital and manufacturing in nature. Digital transformation by GE and Siemens provides such examples.

e) Unintended Consequences

“In January 2007, when Steve Jobs paced the stage and introduced the iphone to the world, not a single observer reacted by saying, “Well, it’s curtains for the taxi industry.” Yet fast forward to 2018 and that appears to be precisely the case”. (pp. 155)[11]. This is an interesting example of unintended consequences in action.

Unintended consequences refer to outcomes that could not have been anticipated or predicted, when a decision is taken. Unintended consequences could appear at the level of economy (as in the 2008 Financial Crises), industry (as in case of social-media platform, where fake news have raised concerns), or a firm (as in case of Amazon discovering use of its’ IT infrastructure, which led to its Amazon Web services business, which also serves as an example of emergent strategy).

informationisation of business and economy made possible through digital technologies, in theory, leads to openness, transparency, greater opportunities and equality. That digital technologies led businesses are increasingly considered as contributing to polarisation and inequities is another example of unintended consequences.

Unintended consequences could arise due to a number of reasons: Inter-connectedness in a system (in this context, economy or markets), makes it harder to predict how different firms or consumers would individually behave and the net impact of their actions on the system. Tough competition, data-based business models, insensitive use of algorithms and a winner-takes-all mindset leads to light touch, if not disregard, to privacy, ethics and contributes to unintended consequences in terms of ethical, social, and economic impact.

Scholars Nitin Nohria and Hemant Taneja[12] argued, “The rapid scaling catalyzed by Moore’s and Metcalfe’s laws have both benefited the technology industry and undermined it by exacerbating its unintended consequences”.

5) What is a Digital Organization?

Whilst the influence of digital technologies – and the information/data that they enable as a strategic asset – on market place, and organizations themselves is appreciated, there is less clarity on what is a digital organization? Are they digitally-native (born) firms, such as Google and Facebook, or they could also include firms, such as Fintechs and autonomous car-manufacturers, such as Tesla, which have both conventional product/service, but an inseparable digital capability?

The question is important, because managing a digital organization, as if it is a manufacturing organization limits the opportunities and gives rise to risks that may impact strategic and competitive performance of the firm. The strategic, organizational and cultural imperatives are different in the two cases, because the nature of resources (traditional as opposed to digital) used to build competitive advantage are different.

This paper takes the view that, for non-digitally-native firms (mostly product and manufacturing driven), there is no set-event, or time-triggers that separate digital firms from non-digital firms. The term digital organization is not a binary construct; instead, it is a relative term, and most organizations are at some point on a spectrum, which has end-points of being “pure traditional” and “pure digital”. Further, the end-point of the digital side (of the spectrum) is constantly extending itself further outward, because digital technologies are constantly evolving and developing.

With this background, this paper proposes a working definition of digital organisation as a firm that has organizational capabilities to create, share and apportion value through digital technologies in ways that is different in either form, scale, or methods relative to organizational current experience, competitive practices or general business standards.

6) Features of a digital organization

This paper builds the perspective that evolution of technologies increasingly resembles a fast-moving digital treadmill, where newer technologies are constantly emerging, and an organization needs to consider digital choices on an ongoing basis as opposed to as a one-time decision. There is no endpoint in the digital side of the spectrum, as newer technologies push the high-end of the spectrum further every now and then. A journey to become a digital organization is therefore an on-going as opposed to a one-off change process.

The following criteria are based on case-studies, existing research and main-stream discussions in terms of where the best practices may be heading. They are also aspirational to some extent, particularly in areas, such as ethics and governance.

Bearing the above in mind, an organization is a digital organization to the extent it meets the following tests.

- It uses digital technology to develop its’ strategy or innovate its business model to create value in ways that are significantly different to industry practices. An organization, which is fairly advanced in its digital capabilities, is one that is able to create sustainable competitive advantage through its use of digital technologies. (“Business strategy test”).

- Its use of digital technology is significantly higher relative to its’ past or its competitors. This use could refer to deploying different types of technologies in varied ways for different needs and value-add purposes within the organization, and also able to integrate them for overall organization benefit. (“Digital strategy test”).

- Its use of digital technologies goes beyond the normal “business as usual digital technology” approach. This means it uses technology to a greater extent and innovative ways for more activities than existing industry norms. This could mean creation of more value for stakeholders, but also to explore more opportunities to engage with varied and emerging stakeholders in new and productive ways than was either not done or not possible previously. (“Stakeholder engagement test”).

- It makes a conscious effort to build a digital culture, which involves, inter-alia, recognizing and adapting to the structural and organizational design imperatives of digital. (“Digital culture test”).

- It considers building digital capabilities a strategic activity and a key part of its culture. At the basic level, digital capabilities refer to the level and application of digital literacy in the firm and digital diversity, but at an advanced level it may include ability to metamorphose digital into general organizational capabilities, such as innovation, superior customer services, fair and responsible management practices, employee well-being and data-centricity. Such organizational capabilities may in turn lead to new business models, novel strategies, and innovative products and services. (“Organizational capabilities test”).

- It uses digital technologies in a way that promotes good governance and ethical values, such as transparency, fairness, equality, diversity and inclusiveness. Viewed in this perspective, an organization, which collects and “sells” data, or have algorithms that limit customers and employees’ sense of transparency, or does not practice “duty of care” is less of a digital organization compared to a firm that has organizational practices that promotes right societal and business values through (say) extensive pre-testing of algorithms and audit practices. (“Ethics and Governance test”).

The criteria above connect to each other in myriad of ways, and are neither mutually exclusive nor collectively exhaustive. Their choice, albeit subjective in nature, reflects the debates and challenges that are becoming increasingly mainstream (such as privacy and ethics). Additional technology specific considerations, such as cybersecurity, green-ness of technologies, use of automated AI led services, algorithms or digital savviness of the Board of Directors are excluded, as they are indirectly incorporated in other tests above.

Above tests also reinforce the point, consistent with observations from various writers, that digital organization and digital transformation is not about technology alone, but about how and to what purposes it is used, and various cultural, leadership and process initiatives needed to leverage it.

7) Main Propositions

The main ideas of this section can be summarised in the form of following propositions:

- Digital technologies enable a different set of resources (“digital resources”) available at scale, very low cost, and at various levels of granularity, complexity and detail. These resources include information and data, but also include digital tools, such as APIs. prediction models, and RPAs.

- Digital resources are different in nature from other resources and economics factors of production, such as capital, land, plant and machinery, and human resources. Digital resources have certain features (such as near zero marginal cost, low transaction cost, network effects, power-law and long-tail based distributions) that make them different.

- The nature of digital resources changes the nature of marketplace and competition (network effects, scaling of firms, synergy and spillovers, platforms and eco-systems). This has implications for strategy, culture and leadership, discussed in later sections.

- Digital technologies change the economics of information and data (and possible other digital resources). This allows –

- A new compact between information, uncertainty and value. In theory, a new business model or strategy is possible, whenever information is available inexpensively at scale to reduce various kinds of uncertainties that users and businesses face.

- New value-creation by integrating and using information that was (earlier) inaccessible, or expensive and resource intensive to organize and process. Micro-financing, delivering aid to vulnerable groups, and new drug discovery for health problems in poor countries are few such examples.

- Organizations are digital to the extent they leverage digital technologies to create new value and build competitive advantage. The level of being digital can be assessed by referencing few criteria set out in the paper.

- These criteria include the extent to which digital technologies lead to strategy development, stakeholder engagement, digital culture, new organizational capabilities, and right ethics and governance.

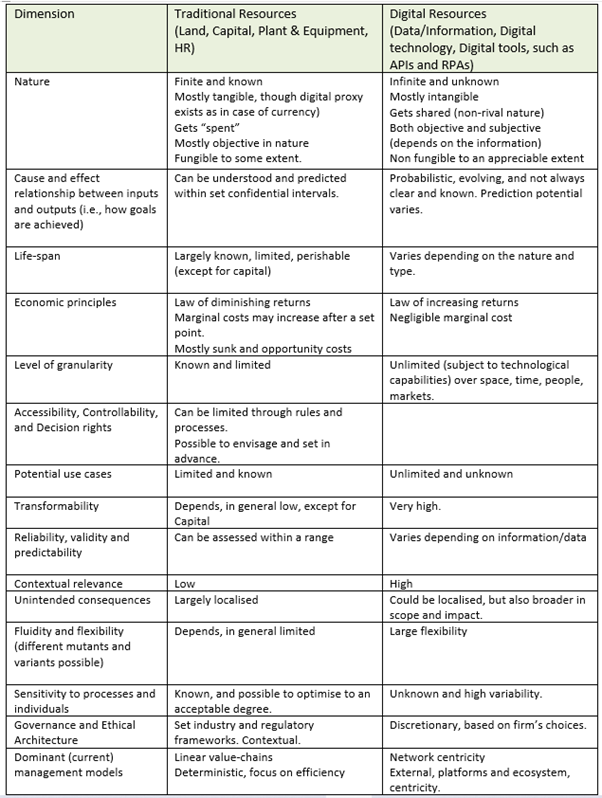

Expanded Table 1

Expanded Table 1 giving additional comparison between traditional resources and digital resources.

References

[1] Bughin, Jacques., Catlin, Tanguy., Hirt, Martin., and Willmot, Paul., (2018). Why digital strategies fail. McKinsey Quarterly. January 2018.

[2] Evans, Philip and Wurster (1997) “Strategy and the New Economics of Information”, Harvard Business Review, September – October 1997.

[3] As above.

[4] As above

[5] Porter, Michael E. and Heppelmann, James E (2015). How Smart, Connected Products Are Transforming Companies. Harvard Business Review. October.

[6] Bughin, Jacques., Catlin, Tanguy., Hirt, Martin., and Willmot, Paul., (2018). Why digital strategies fail. McKinsey Quarterly. January 2018.

[7] Malnight, Thomas W. and Buche, Ivy. (2022). “The Strategic Advantage of Incumbency. How to unleash the power of complexity, trust, and commitment”, Harvard Business Review. January – February 2022.

[8] Ransbotham, Sam., Khodabandeh, Shervin., fehling, Ronny., LaFountain, Burt, and Kiron, David.(2019) “Winning With AI: Pioneers Combine Strategy, Organizational Behavior and Technology. MIT Sloan Management Review. October 2019. Research Report in collaboration with BCG.

[9] Brynjolfsson, Erik and McAfee, Andrew. The Second Machine Age. Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. (London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2014)

[10] Bughin, Jacques., Catlin, Tanguy., Hirt, Martin., and Willmot, Paul., (2018). Why digital strategies fail. McKinsey Quarterly. January 2018.

[11] Agrawal, Ajay., Gans, Joshua., and Goldfarb, Avi. (2018). Prediction Machines: The Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence. Harvard Business review Press. Massachusetts: Boston.

[12] Nohria, Nitin and Taneja, Hemant (2021) Managing the Unintended Consequences of Your Innovations”.