China’s Gilded Age by Professor Yuen Yuen Ang, Cambridge University Press, May 2020

China’s Gilded Age is a fabulous book by University Of Michigan, Professor Yuen Yuen Ang. Part academic treatise and part journalistic, this short read of 200 pages is not only informative but ends up raising several important questions of the nexus between Corruption and Growth by taking China as an example. It also asks why the salaries of bureaucrats are not generally performance-linked (i.e., economic growth, tax collections, etc.). As she shows, this pay structure has worked wonders in China. Finally, there is an essential question of emerging democracies and economies copying first world practices in toto without modifying them for their unique circumstances (and forgetting that the first world economies themselves took centuries to reach where they are now).

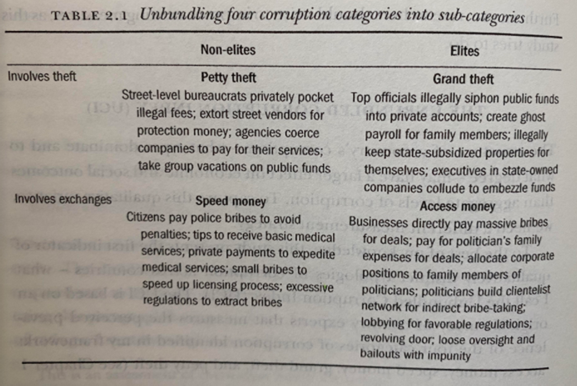

The book starts by challenging the typical notion that corruption hurts economic growth and that this is what ails all emerging market economies. The author raises the question if that is indeed the case, then how and why China grew so rapidly. The author attempts to answer this question by developing a unique framework to better understand the notion of corruption in its myriad forms and then using it to show that not all forms of corruption are the same. While headline corruption numbers from traditional sources like CPI (Corruption Perception Index, managed by Transparency International) may look the same, underlying forms of corruption can differ significantly. Using her unique expert survey aiming to unbundle the nature of corruption, the author segregates corruption into four types which are highlighted below –

The author highlights that China and India, which score similarly on CPI, exhibit very different forms of corruption. In India, speed money dominates – the need for paying bribes to lower-level bureaucracy for getting even basic things done. In contrast, in China, access money – the need to pay massive direct and indirect bribes (running into millions of dollars) to elite politicians and bureaucrats, dominates.

It is not difficult to understand why this is the case. In an authoritarian system like China, politicians have sweeping powers that can’t even be imagined in a democratic setup. Hence, the need to court favors of elite politics becomes essential. In contrast, in a setup like India, where politicians can change every few years, lower-level bureaucracy remains permanently and can seek smaller rents.

That is not to say that all democratic systems exhibit a prevalence of speed money. It is somewhat more a function of the democracy’s economic state. For example, although in the United States speed money has been eliminated through almost a century of administrative and political reform, access money is prevalent at a magnitude similar to China. While in China, it is rather crude through personal relationships, in the US, it takes more sophisticated forms like corporate lobbying, relvolving doors, etc.

But while the prevalence of access money can be easily understood, a question remains – how China put a lid on other forms of corruption especially speed money and petty thefts? The book shows that until 2000, these forms of corruption were quite prevalent in China, but then they were controlled after a specific set of administrative reforms were instituted in 2000. The critical part of these reforms was the adoption of profit-sharing practices for bureaucrats. Millions of bureaucrats’ payoffs were linked to their locality’s tax and agency’s non-tax collection to incentivize economic performance. Bureaucrats, who are pretty intelligent, quickly realized it is better to foster economic growth and raise tax collection longer than seeking rents. Based on some samples, as much as 70% of official salaries are linked to economic performance.

All this doesn’t mean access money is without its own set of problems. In the case of China, using case studies of Bo Xilai and Ji Janye author shows how this form of corruption leads to skewed credit growth, monopoly privileges, and regulatory exemptions. While these activities raise annual growth, they also result in the building of systemic fault lines, which can erupt at any time. To address precisely this risk, President Xi initiated the largest anti-corruption drive in China’s history. But this has resulted in a misalignment between political and economic goals. The ensuing harsh scrutiny has made officials risk-averse – preferring to do nothing and avoid blame instead of signing off initiatives. At the same time, the administration’s preference for a more substantial role of the state has increased the necessity of proactive bureaucracy.

The author finally tries to generate some parallels to the United States’ gilded age of the late 1800s. But I think the linkage is weak, but more importantly, not essential to make. The book’s material stands firmly even without this linkage.