My Frame of Reference for Strategic Choices in an Industry-in-Transition

I work for the world’s largest lighting firm at a time when the lighting industry is undergoing a major transition, caused by growth in urbanisation, changes in technology and the evolution of consumer preferences as their incomes have grown.

The emergence of new technology, particularly during the last two decades, has been a major factor driving supplier as well as consumer choices. While the incandescent (light emission through heating of filament) lamps have been the source of general lighting for nearly a century, the CFLi (compact fluorescent) products have been in the market only for about 20 years, with commercial production having begun on 1995. CFLi products have not only been more energy efficient, they have also been more durable. Introduction of LED (Light Emitting Diode) technology in lighting applications, less than a decade old in the consumer market, has not only equalled the energy efficiency and surpassed the durability standards set by CFLi technology, it has also provided an opportunity for consumers to experience millions of colour and light-level variations (dimmability) using the same lamp, which was not possible with incandescent lamps or with CFLi lamps.

Increased Uncertainty and Complexity

At present, the lighting industry, across the world, is offering products based on all three technologies. Some of the developed countries have phased out the production and sale of incandescent lamps completely, have been discouraging CFLi production and sale and are encouraging the adoption of LED technology. At the same time, incandescent and CFLi products are the main source of general lighting in many low- and middle-income markets, as they are simply much more affordable for a lot of people in these countries.

Considering the advantages of LED technology, a low-income country like India, is also trying to accelerate LED adoption through policies involving financial incentives and provision of risk-capital. While the governments across the world are influencing the choice of technology and products, the consumers are yet to give up on incandescent or CFLi lamps in many markets. In some situations, it is simply the high initial purchase cost (investment) of LED that is impacting consumer choices and in others it is the preference for certain kind of light (warm yellow of incandescent and white or yellow of CFLi).

Commercial, industrial and institutional consumers have adopted newer technology sooner, as they value cost and energy savings from the longer-term perspective. At the same time, the concerns about the environment impact of energy usage has resulted in faster adoption of CFLi and LED products among business as well as household consumers in some countries.

The government intervention in the market is being driven by the impact on environment and savings in energy costs in situations where the government is either a consumer or provides generation and/or consumption subsidies. For example, the government can reduce the production subsidy over time by not buying the subsidised power, if the consumption levels are coming down with the use of LED technology. Similarly, the government realises immediate savings in countries where the consumption is subsidised.

Yet another characteristic of this market is the impact of scale in manufacturing and the fragmentation of production and supply chain given the nature of technology involved. In addition, some of the module components were in use in other industries much before LED technology was adopted in the lighting industry. In other words, the volume of component production across industries allowed the existing benefits of scale to come to the lighting industry sooner and the natural size (production of hundreds of millions of lamps per year) of the lighting market reinforced the scale advantage at an even faster rate.

Premises underlying the Frame of Reference

My role requires me to maintain and grow market share in markets where the LED adoption is progressing at a fast pace and continue to invest in growing the market and our share in areas where LED adoption is slow, or the penetration rate is still very low.

The premises that have guided my and my team’s thinking are:

I. Reason to Buy

- Consumers will move to new technology only if the new technology-based products provide greater benefits for a given price (higher or lower).

- If we expect the consumers to pay higher price, the value of benefits should be consistent with the price of new technology products.

- Some consumers are willing to pay a high price, if the new technology serves a purpose close to their heart, e.g., variety of colours that LED products offer or their being more environment friendly.

II. Price Points

- Each market has a price-point that can accelerate demand by making products affordable.

- Each market also has price-point that can serve as the tipping point and accelerate switch to a new technology. In other words, some of the consumers may buy the new product even if the price is higher than the existing technology-based products.

III. Role of Government in Technology Adoption

- Government subsidies, regulatory provisions and market interventions can help accelerate demand.

- Government market intervention can also destroy the economics of business, if the intervention becomes too aggressive and/or the government persists with the intervention for too long, thereby destroying industry profitability.

IV. Impact of Market Intervention by Government

- If the government’s market intervention results in the entry of many new players, we can expect some of them to focus on short-term profits.

- The use of cost-based (lowest-price based purchases) decision criteria by the government may impact of the quality of products being offered by many players.

- If the consumer has experienced poor quality supply during the government intervention period, we can expect the consumer to recognise the value of brand during the replacement cycle, but they could also be put off by the bad experience with the new technology.

- The government may help create new markets through intervention by offering new technology products in areas where people don’t have electricity.

V. Differential Pace of Technology Adoption

- Some countries or segments adopt technology faster than others, irrespective of the price-value proposition.

- While the pace of adoption may be similar in many situations, but the reasons can be different, e.g. environment impact in one case and simply the willingness to experiment with new technology and products in another.

VI. Industry’s Role of Technology Transition

- Voluntary restriction of supply and phased withdrawing can help smoothen the transition, i.e., help lessen the impact of discontinuities caused by regulatory bans.

VII. Nature of Ownership in B2B Market and its Impact on Choices

- While the government is helping adoption of technology on one hand by providing incentives, there is no guarantee that the buyers in all government departments will use the same frame (decision criteria) as the policy-making institutions.

- While the private-sector buyers, more often, use financial criteria to make choices, the decision process can get accelerated if we reach out to the functions and roles (e.g., CFOs) that are quick to see the impact of proposed choices on their role’s contribution.

- Some decision-makers (particularly in the public sector) tend to be risk-averse and use shorter investment horizon, e.g., a public-sector decision maker tends to hesitate if the benefits accrue during the years which extend beyond their years’ in a role or the office.

- Organisation culture plays an important role in decision making, as some organisations encourage their leadership teams to work towards building long-term profitability.

VIII. Inherent Value of Technology and the Selling-proposition

- We need a conscious effort to get consumers to see value in new features (dimmability and multiple-colour features) and be willing to pay for them.

- The consumer may often say that the existing product ‘serves the purpose’, why should we shift is the view in some segments.

- The civil-society (Non-Government) organisations concerned about impact of consumption on environment may help accelerate adoption of technology in some situations.

IX. Profit Structure of Business (or Economics of Business)

- We may experience an initial rush of players in expectation of high profit during the early years.

- Industry may consolidate faster than expected if the new players discover that the structural profitability is lower than conventional (existing) technology, i.e., if the pot of gold is smaller than expected.

- On realisation that the structural profitability is low, the new entrants or the potential new entrants may shy away from making long-term investments.

X. Role of Distribution in Market Evolution

- If the nature of consumption undergoes a change, we may need to invest in newer channels, e.g., the shifts in consumption from lamps to luminaires (shift from a standard product to a more value-added product) resulted in e-commerce becoming an important channel for distribution.

- After the introduction of LED lamps, which is seen as technology-based, high-value product, the purchases begin to happen using online platforms, which is another example of a shift in buying behaviour with change in the nature of consumption (the new technology product in this case).

- Retail distribution (exclusive retail stores) set up for luminaire sales also started selling high-value LED lamp products, as the economics of distribution changes and the partner recognises the potential to earn.

- A long-term relationship with partners strengthens the resolve to navigate uncertainty associated with a transition.

- Inventory matters (what gets displayed is what gets sold) and therefore inventory investment required for new-technology product is high. Distribution needs to manage inventory more actively without sacrificing sales of existing or the new products. Phase in and phase out by the company and distributors becomes critical

- It is important to track secondary sales, particularly in transition situations where inventory matters. A distribution management system (preferably technology-based solution) is critical to ensure that the cost of transition remains low.

- If one is late in leveraging (adopting) technology in distribution, we have an opportunity to learn from others and it pays to hire people with experience from other industries.

- Sales teams take time to align their effort to managing secondary sales versus primary sales, but once they do, they start managing sell- out at the retailer’s location rather than just sell-in at the distributor or wholesaler’s place.

XI. Business and Portfolio Mix

- It is important to balance the portfolio to sell to large as well as small projects so that the negative impact of economic and business cycles and the natural lumpiness of large projects is minimal.

- It helps to involve distribution partners to expand geographic as well as customer coverage, particularly for reaching out to small customers.

- We may set up segment specific sales team to increase the intensity of sales effort.

XII. Changes in Nature of Consumption

- The Lighting consumer is becoming more of a lifestyle buyer rather than a product buyer, requiring us to change the strategy across the entire value-chain.

- B2B customers need to be informed of the advantages of transitioning from buying products to buying services and solutions, and hence there is a need for a change in strategy.

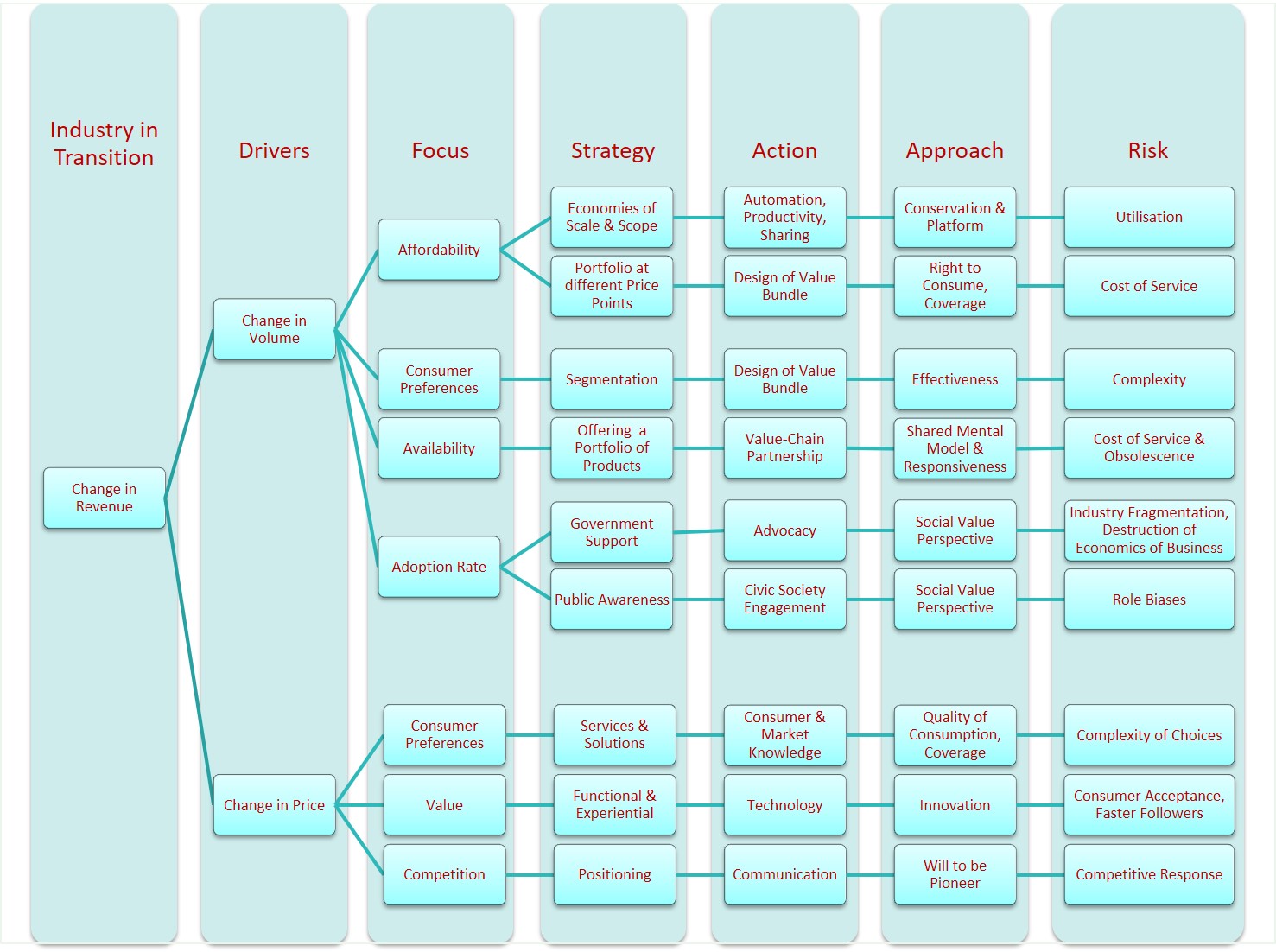

If I were to articulate my ‘mental model’ or the ‘frame of reference’ for strategic choices in an industry in transition, I would build it around the following few ideas:

- Value Matters, so does Price. Each market has its own price point, which enables acceleration of demand or switching from one technology/product to another. Reasons may vary by the market.

- Pricing with premium over value is feasible, if the product or a service serves a purpose close to a consumer’s heart.

- Technology can help convert a near-commodity product into a life-style solution, allowing us to segment the market and offer a completely different price-value proposition.

- Government support can help accelerate growth, but it comes with the risk of destroying the economics of a business – an unintended consequence.

- While the government sector is expected to take a long-term view on price-value proposition, helping industry deal with uncertainty arising from changes in technology, it depends on the decision-maker’s willingness to take risk.

- Consumer’s pace of adoption varies by the market and reason for variation can be very different from one market to another. A public debate on value can influence choices.

- Irrational exuberance is a known phenomenon and is a double-edged sword. But it pays to be a long-term investor in a situation characterised by ‘get-rich, quick players’.

- It pays if the producer and the distribution partners have shared mental-model of business, i.e., they row in the same direction and are willing to take the required investment-risk during the transition.

Chart: My Mental Model or Frame of Reference

While the articulation of my ‘frame of reference’ and its underlying premises is abstract, it has been based on the situations that I have had to deal with during the last 20+ years across different roles in different businesses – both B2B and B2C situations – be it in paints, consumer durables, financial services or lighting.

Home Reflective Practice Research Publications Mental Model My Frame of Reference for Strategic Choices in an Industry-in-Transition My Frame of Reference for Strategic Choices in an Industry-in-Transition I work for the world’s largest lighting firm at a time when the lighting industry is undergoing a major transition, caused by growth in urbanisation, changes in technology…